Mapping Current Trends: The Asphalt Frontier

Text and maps by CatComm collaborator and urban planner Jake Cummings, result of his Masters thesis at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design in May 2013:

The word asfaltização in Portuguese refers to the introduction of asphalt to Rio’s favelas—the self-built settlements that historically have lacked not just road paving but a host of city services. Asfaltização is also a metaphor for the introduction of conventional ways of doing business, and market economies that can price low-income residents out of their own neighborhoods. With the coming FIFA 2014 World Cup and 2016 Summer Olympics events, a coalition of government and private interests is expanding its control along what I call the “Asphalt Frontier.” This public-private partnership is at work paving a safe environment for the investment spree accorded these mega-events. Absent fairer and better planning, it is also worsening the segregation of Rio by income and social class.

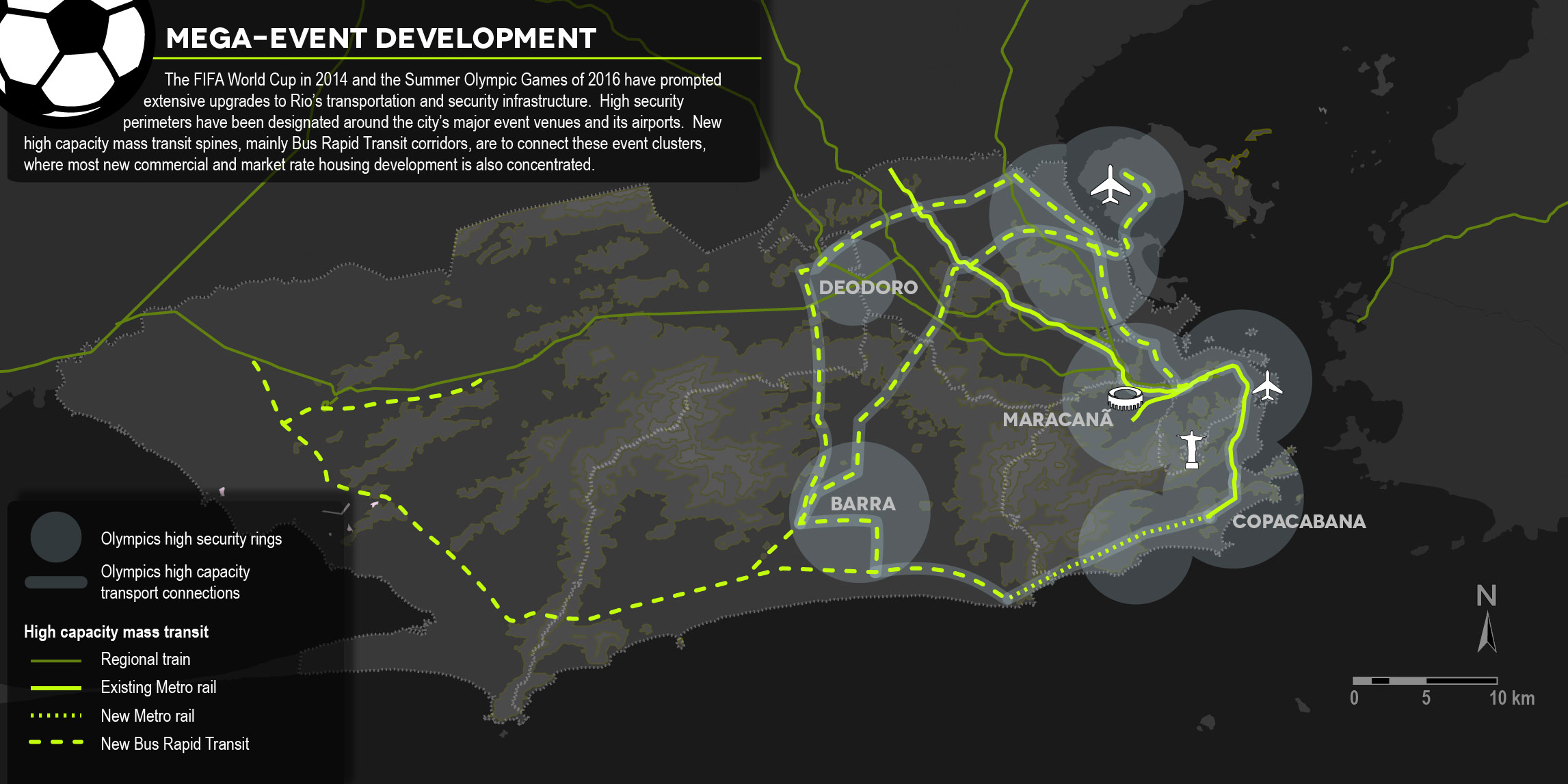

Mega-Event Development

The FIFA World Cup in 2014 and the Summer Olympic Games of 2016 have prompted extensive upgrades to Rio’s transportation and security infrastructure. High security perimeters have been designated around the city’s major event venues and its airports. New high capacity mass transit spines, mainly Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) corridors, are to connect these event clusters, where most new commercial and market rate housing development is also concentrated.

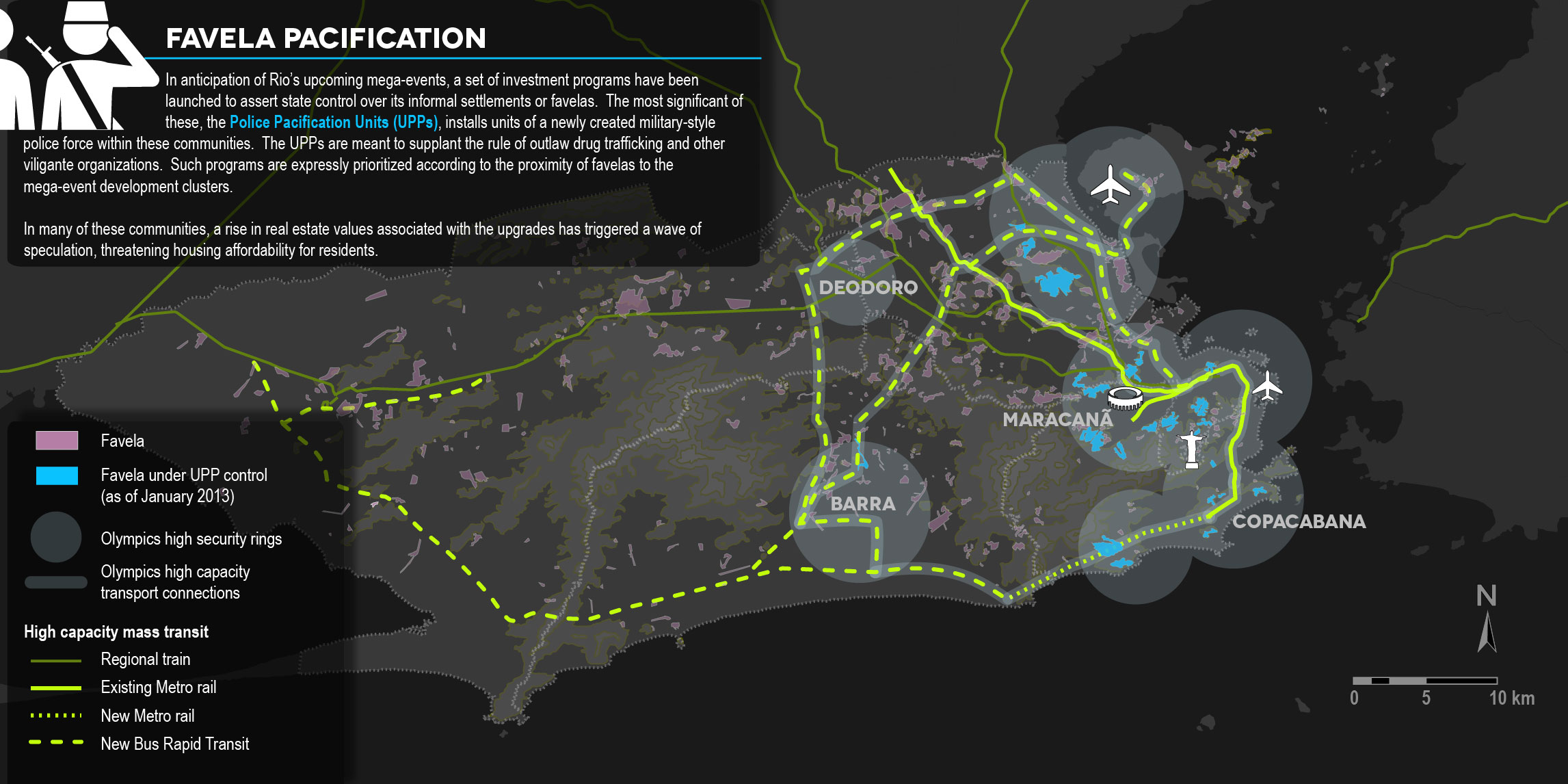

Favela Pacification

In anticipation of Rio’s upcoming mega-events, a set of investment programs have been launched to assert state control over its informal settlements or favelas. The most significant of these, the Police Pacification Units (UPPs), installs units of a newly created military-style police force within these communities. The UPPs are meant to supplant the rule of outlaw drug trafficking and other vigilante organizations. Such programs are expressly prioritized according to the proximity of favelas to the mega-event development clusters. In many of these communities, a rise in real estate values associated with the upgrades has triggered a wave of speculation, threatening housing affordability for residents.

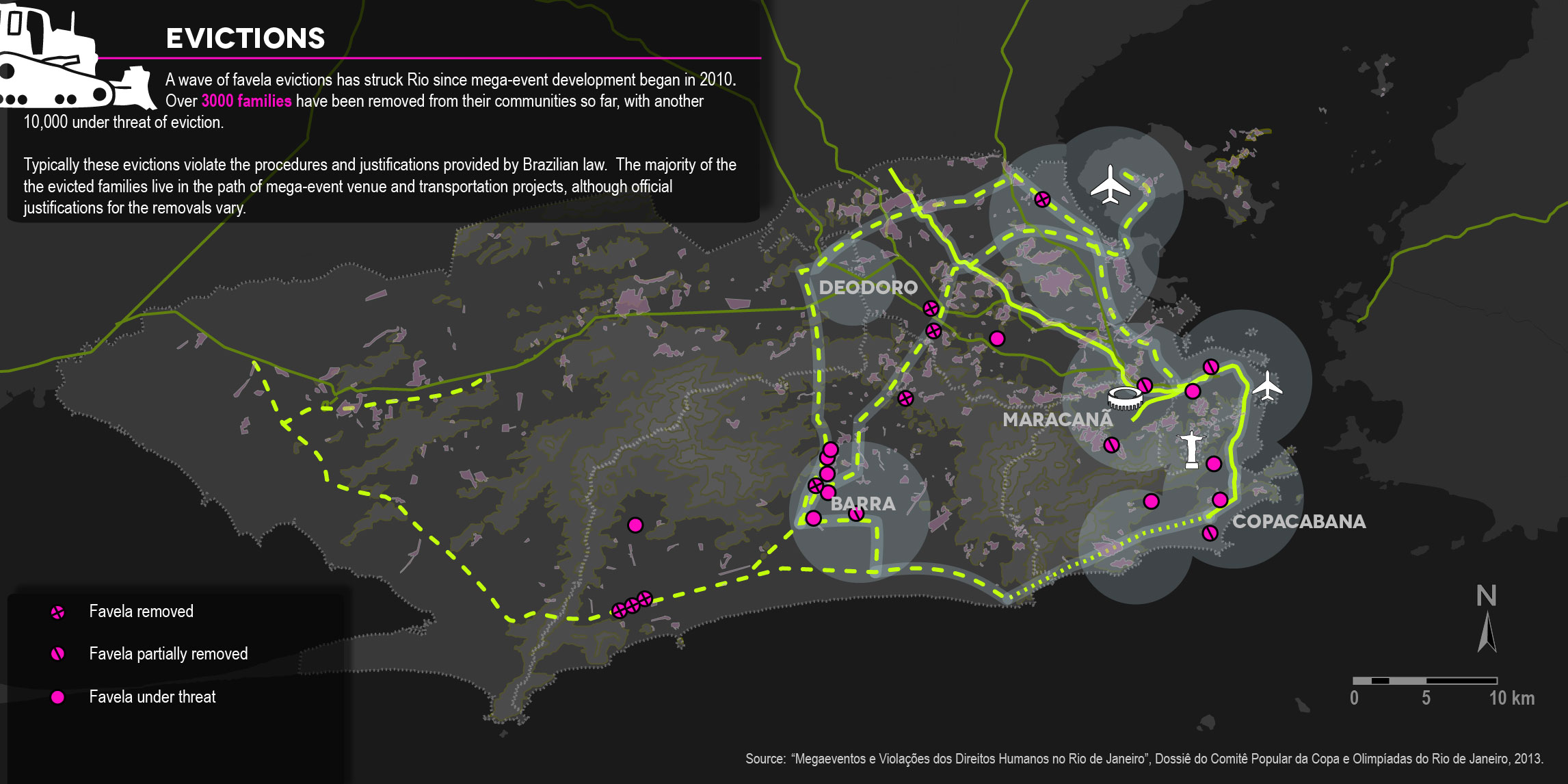

Evictions

A wave of favela evictions has struck Rio since mega-event development began in 2010. Over 3000 families have been removed from their communities so far, with another 10,000 under threat of eviction. Typically these evictions violate the procedures and justifications provided by Brazilian law. The majority of evicted families live in the path of mega-event venue and transportation projects, although official justifications for removals vary.

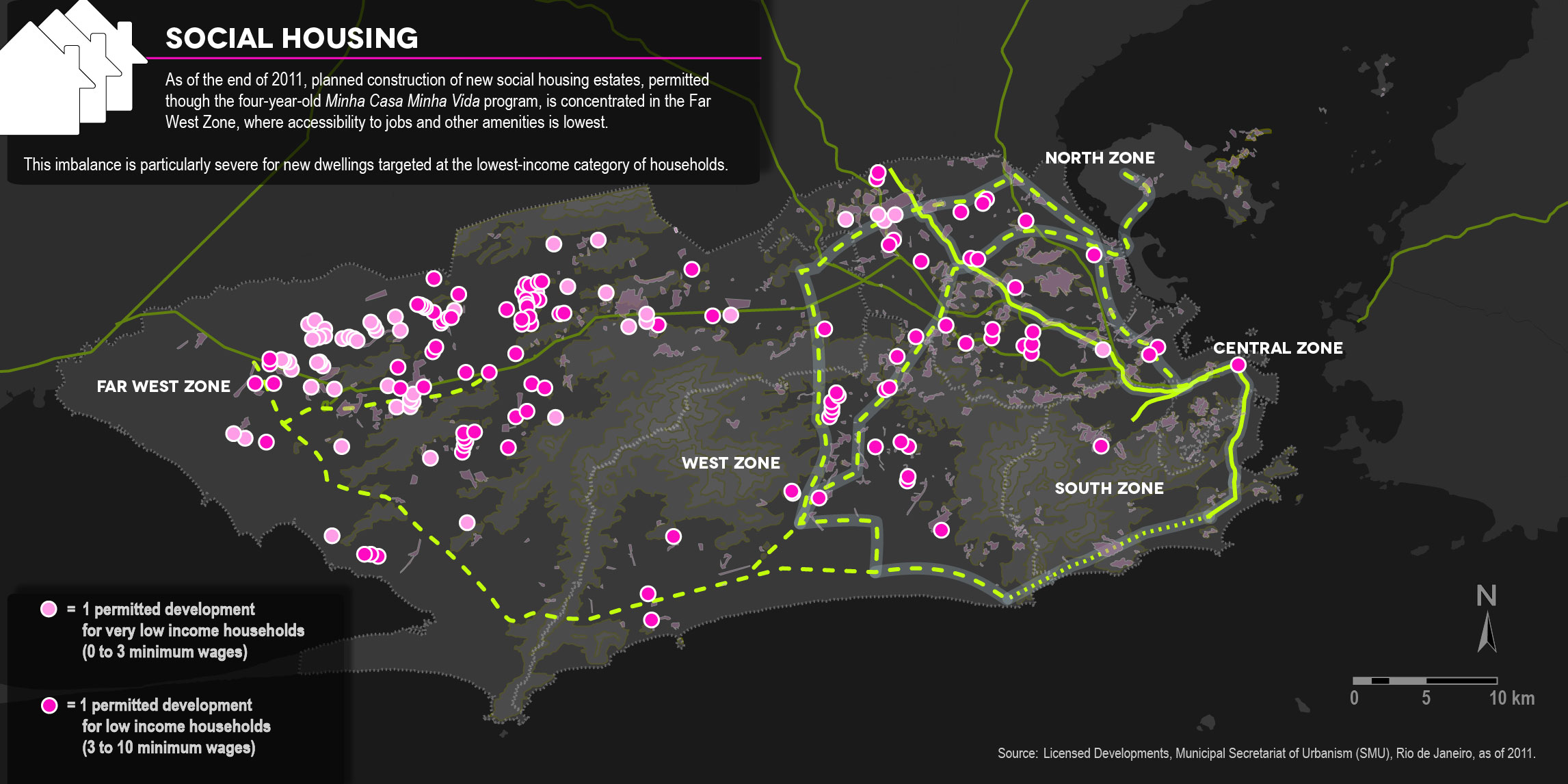

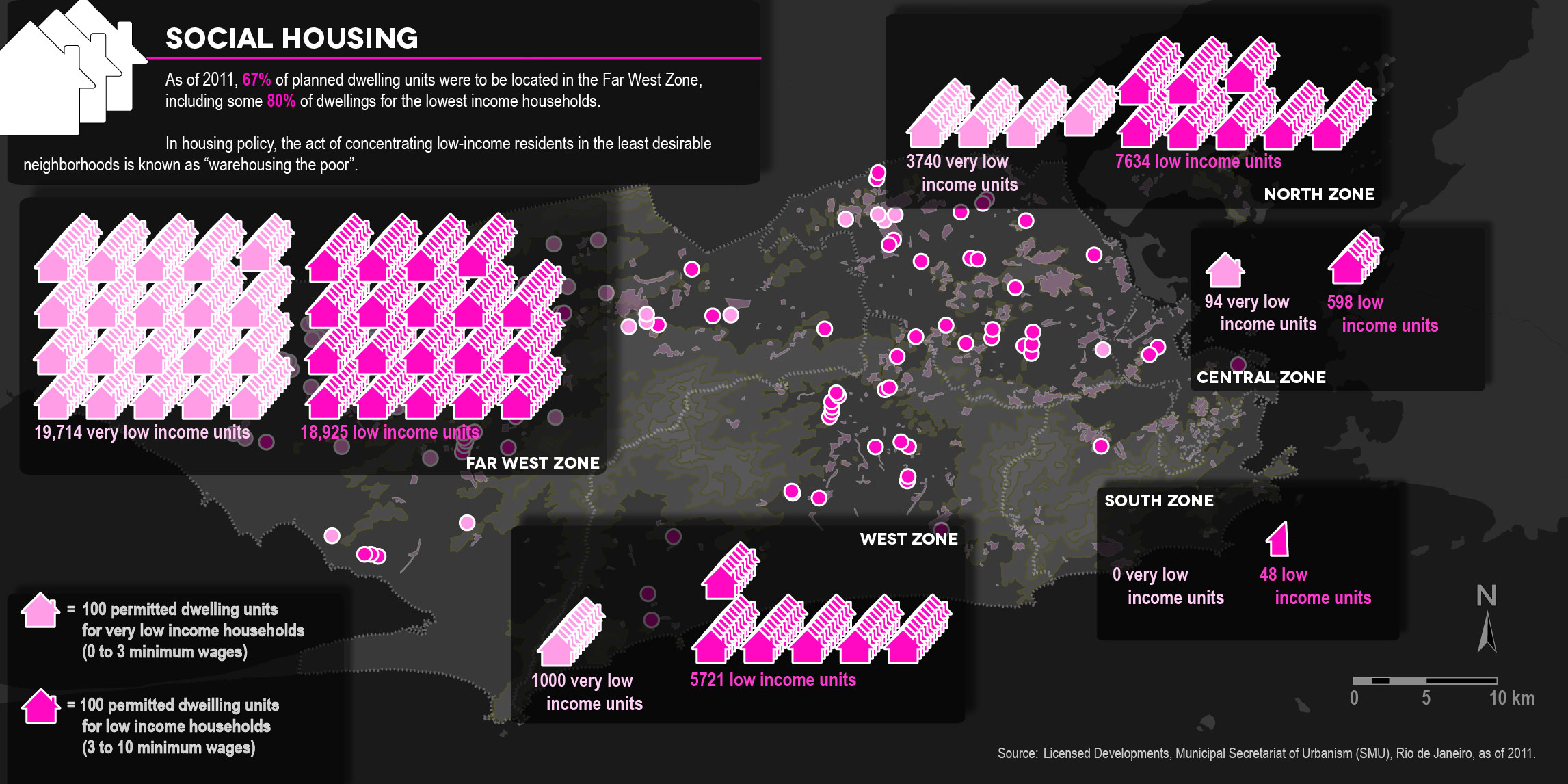

Social Housing

As of the end of 2011, planned construction of new social housing estates, permitted though the four-year-old Minha Casa Minha Vida program, was concentrated in the Far West Zone, where accessibility to jobs and other amenities is lowest. This imbalance is particularly severe for new dwellings targeted at the lowest-income category of households.

As of 2011, 67% of planned dwelling units were to be located in the Far West Zone, including some 80% of dwellings for the lowest income households. In housing policy, the act of concentrating low-income residents in least desirable neighborhoods is known as “warehousing the poor.”

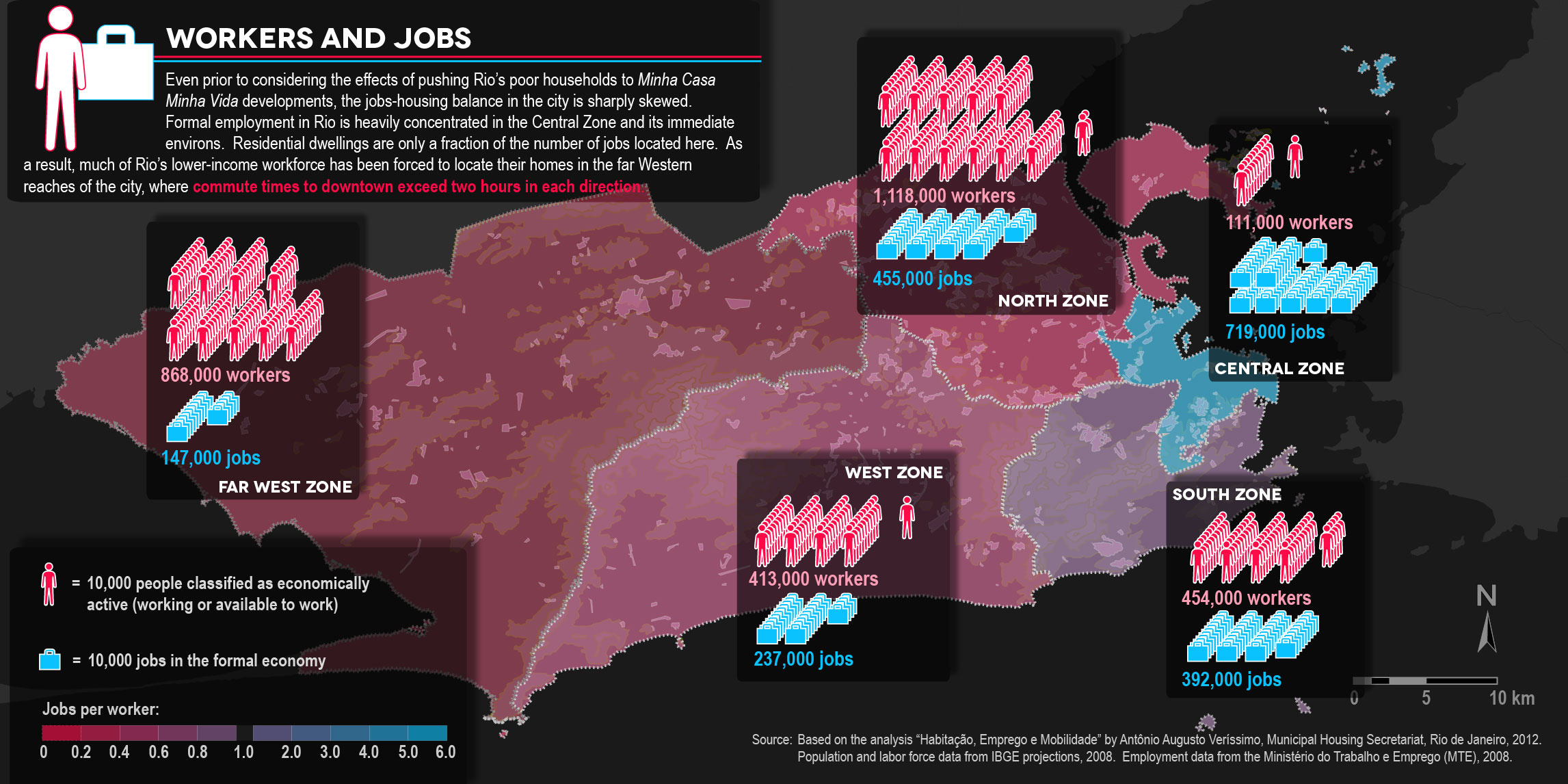

Workers and Jobs

Even prior to considering the effects of pushing Rio’s poor households to Minha Casa Minha Vida developments, the jobs-housing balance in the city is sharply skewed. Formal employment in Rio is heavily concentrated in the Central Zone and its immediate environs. Residential dwellings are only a fraction of the number of jobs located here. As a result, much of Rio’s lower-income workforce has been forced to locate their homes in the far Western reaches of the city, where commute times to downtown exceed two hours in each direction.