3rd Sustainable Favela Network Exchange: Agroforestry in Rio’s Densely Populated North Zone

The Sustainable Favela Network (SFN) is a project of Catalytic Communities (CatComm) designed to build solidarity networks, bring visibility, and develop joint actions to support the expansion of community-based initiatives that strengthen environmental sustainability and social resilience in favelas across the Rio de Janeiro Metropolitan Region. The project began with the 2012 film Favela as a Sustainable Model, followed in 2017 by the mapping of 111 sustainability initiatives and the publication of a final report analyzing the results.

In 2018, the project organized on-site exchanges among eight of the oldest and most established organizations that were mapped in the Sustainable Favela Network (one of which is the subject of this article), followed by a full-day exchange with the entire network that took place on November 10. The eight participants in the on-site exchanges featured in this series include six community-based organizations: the Vale Encantado Cooperative in Alto da Boa Vista, EccoVida in Honório Gurgel, Verdejar in Engenho da Rainha and Complexo do Alemão, Quilombo do Camorim in Jacarepaguá, ReciclAção in Morro dos Prazeres, and Alfazendo’s Eco Network in City of God. In addition, the exchanges visited two broader initiatives focusing beyond favelas with extensive experience in sustainability: Onda Verde in Nova Iguaçu and the Sepetiba Ecomuseum. The program is supported by the Heinrich Böll Foundation Brazil.

Watch the video that accompanies the exchanges featured in this series by clicking here.

Third Exchange Begins in the Shade of the Serra da Misericórdia

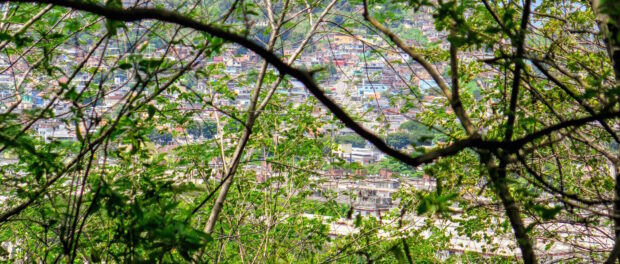

As members of the Sustainable Favela Network (SFN) arrived at the small community of Sérgio Silva in Rio de Janeiro’s Engenho da Rainha neighborhood on the morning of Saturday, October 13, the sun had already begun to beat down on the pavement. The moment the group arrived at Verdejar’s headquarters, however, a cool breeze replaced the heat under the shade of the Serra da Misericórdia urban forest.

This shade was not easily won: for over twenty years, Verdejar has been fighting to reforest, then protect, the largest remaining forested area in Rio’s North Zone—a densely populated region with the least green space per capita in the city.

Verdejar member Patricia Lima explained that the organization currently “works in various languages. We work with ecology; audio-visual [production], theater, photography work… [healthy] food,” as well as with “low-cost socio-environmental technology” including solar-based water heating and rainwater catchment. The organization is focused on rebuilding its headquarters after their previous center was demolished by Rio’s electric utility Light, and on “being closer to the community.” They have built a community garden, are in the process of constructing an oven and stove for an open and open-air kitchen, and provide environmental education for local children.

To begin the day, SFN members from ReciclAction in Morro dos Prazeres, the Vale Encantado Cooperative in Alto da Boa Vista, Ecco Vida in Honório Gurgel, Onda Verde in Nova Iguaçu, and the Sepetiba Ecomuseum introduced themselves and shared what they had taken away from the first two exchanges. Otávio Barros, from Vale Encantado, described his excitement at seeing projects similar to his own in communities across the city, while Helio Vanderlei from Onda Verde observed that “everything starts with people’s resistance. People dedicate their lives—whether to environmental issues, mobilization, training others, or environmental education.” Vanderlei elaborated: “There is fundamental resistance in these communities… So the network is essential because it builds this interrelationship between history and life—histories of social transformation, histories of resistance, inadequate public policies [constructed] without listening to and understanding the local population, be it in Alto da Boa Vista, Morro dos Prazeres, the Baixada Fluminense, or Complexo do Alemão… We are all resistant community revolutionaries who believe in social transformation.”

Verdejar’s tour of social transformation in Sérgio Silva began with their community garden, where residents can visit and collect fresh organic food. Every Wednesday morning, Verdejar invites the public to visit the garden and help maintain the space: anyone is welcome to bring organic waste materials for the garden’s compost in exchange for local produce. Verdejar member Rodrigo Morelato explained that the organization is planning to conduct a community census to determine which types of produce locals would like to see from the garden. SFN members suggested creating plant labels, or even a registry, in order to keep track of which vegetables are most popular among residents. Behind the community garden is Verdejar’s collective space, which is currently under construction but will soon include a pizza oven, stove, and activities for children. When the “coexistence space” is complete, the team plans to host a homemade pizza night using ingredients from the community garden.

Discovering Verdejar’s History Through its Hiking Trails

Surrounding Verdejar’s headquarters is lush vegetation that the organization planted in its early days when members were focused on reforestation, and trails they created and now maintain for local use as well as to lead guided tours for visitors. Lima explained that due to a lack of government investment in preserving the Serra da Misericórdia, protecting the green space is “a daily struggle,” but that “we continue here, resisting in order to keep this green space alive, preserved, and beautiful.” High levels of violence in the North Zone have made using the trails even more difficult. Morelato has counted at least three public hikes that Verdejar had planned but ultimately canceled due to police operations in nearby areas. Sérgio Silva resident and Verdejar member Álvaro Vinicius Azevedo explained that he and his neighbors have less contact with the forest due to this insecurity. Recalling his memories of exploring the forest as a child, Azevedo described: “At five or six years old, I would hike all around here. I know this whole area. It’s like our backyard, an extension of our home.”

In Morelato’s words, “The trails were very important [to our work]. Now, we can’t use them much because of the violence. The hike is magical: it tells stories of these places, of these trees. It’s what changes people’s perspective about being human. And it’s what brings people here [to visit Verdejar and the Serra da Misericórdia].”

As Lima and Morelato directed the SFN group to the nearest trailhead, longtime Verdejar member Zolmir Figueiredo discussed the history of the Serra da Misericórdia: how its location in a part of Rio typically neglected by local government led to its exploitation, how groups such as Verdejar—led by its late founder, Luiz Poeta—fought to achieve recognition as an Area of Environmental Protection and Urban Recuperation (APARU), and how public authorities have failed to translate this legal action into material benefits for the environment and surrounding communities.

In Figueiredo’s words, before Verdejar was founded 21 years ago, “the Serra da Misericórdia wasn’t recognized—it was a forgotten area within the city of Rio… It was an area of mineral exploitation, informal occupation, and an area to throw away waste.” Government neglect combined with the forest’s location next to a landfill led to frequent fires. Luiz Poeta initially created Verdejar to address this threat through community-led reforestation. It was through the advocacy of Verdejar, along with other local institutions, that Rio’s government named the Serra da Misericórdia an environmentally-protected area. However, according to Figueiredo, “In reality, the government never did anything… So there is a master plan for the Serra da Misericórdia Municipal Park, but it’s only on paper. There’s no interest from the government, from the state, from the City, to push this project forward… And those of us [with Verdejar], we’ve been here this whole time.”

Building Green Space, Community, and a Shared Future

Verdejar’s all-volunteer team works at two headquarters in the North Zone: one in Engenho da Rainha—connected to Complexo do Alemão by the Serra da Misericórdia—and the other in Olaria’s Morro da Esperança. One of Verdejar’s challenges is encouraging more local involvement in their projects and building a sense of collective awareness about the importance of the Serra da Misericórdia. While housing is often perceived to conflict with environmental conservation, the Verdejar team wants to show communities in the forest’s perimeter that they can indeed coexist with the natural environment, generating positive impacts for the health of both the local population and ecological systems. While the organization currently lacks the labor force and government support needed to manage the Serra da Misericórdia’s vast agroforest, the organization is focused on increasing community involvement in its projects. Lima explained that a series of in-home gardening workshops helped the Verdejar team get to know more residents and encourage them to develop their own green spaces at home. While the Verdejar team is confident that locals are familiar with Verdejar, they want to create a greater sense of community ownership. In Lima’s words, “We are creating a network in the streets… for the community to know that we are here… Because we’re not here doing all of this for us. We’re doing it for them, for them to take advantage of everything here.”

As the SFN group returned from its hike to Verdejar’s headquarters, participants exchanged ideas about the organization’s goals and challenges. EccoVida representative Marcele Ribeiro offered to put the team in touch with a friend who spoke at a recent Zero Waste event about agroforest management, while Vale Encantado’s Otávio Barros suggested that the organization partner with students at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) to expand their volunteer base and scope of expertise. Meanwhile, Onda Verde’s Helio Vanderlei suggested the team create a sign with a map outlining the forest, its surrounding communities, and the areas where Verdejar works, explaining the importance of creating a “geographic vision of the territory… For us to locate ourselves in. We all value what we see—we don’t value what we [only] hear.”

Ideas continued to flow as SFN participants filtered from Verdejar’s forested headquarters into the midday heat, continuing on to EccoVida—another grassroots North Zone initiative with a long history of working towards socio-environmental sustainability. Before leaving, however, representatives from both Onda Verde and the Sepetiba Ecomuseum shared ideas and experiences with Verdejar’s representatives about everything from photography projects to environmental education—conversations that ensured that the morning’s exchange was far from over.

View our photos from the exchange (or click here for album):

Read up on all of the 2018 Sustainable Favela Network exchanges here.