New Paths for Building Sustainable Cities: The Potential of Collective Land Management Based on the Community Land Trust

Clique aqui para Portug uês

uês

As part of the UN’s Urban October’s Urban Circuit 2022 and World CLT Day 2022, the Favela Community Land Trust Project* held the webinar ‘New Paths for Building Sustainable Cities: The Potential of Collective Land Management Based on the Community Land Trust’ on October 27, 2022. The event was supported by UN Habitat, World Habitat, Urbamonde, and the Center for CLT Innovation. It was moderated by Tarcyla Fidalgo—lawyer, urban planner and coordinator of the Favela-CLT Project.

Community leaders, activists, and representatives of civil society organizations—in Brazil and internationally—with experience in community development, self-managed housing, and Community Land Trusts (CLT), especially in the context of the Global South, presented at the New Paths for Building Sustainable Cities: The Potential of Collective Land Management Based on the Community Land Trust webinar. Participants presented on how the CLT model can strengthen community control over land and support resident-led development.

The CLT is a model of land regularization and collective land management in which the structures belong to individuals and the land belongs to the community. This system combines collective and individual interests to ensure continual affordable housing for low-income populations while they benefit from the development that follows. The goal is to protect residents and communities from eviction and limit real estate speculation, minimizing the risks of gentrification. The benefits of the model extend beyond housing, promoting community empowerment so residents remain autonomous over their future after formalization has occurred.

The event began with a presentation by Tarcyla Fidalgo on the Community Land Trust as an alternative model to produce affordable housing in order to achieve Sustainable Development Goal 11: to make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable.

Session 1: Presentations by Professionals Working on Community Land Management Projects

In the context of Brazil and its favelas, Theresa Williamson, executive director of Catalytic Communities (CatComm), described how the CLT model was first introduced in Rio de Janeiro. In the early 2010s, the demand for a land regularization model that would ensure the permanent rights of communities to remain within their territories was urgent due to the evictions taking place under the pretext of the city hosting two mega-events—the World Cup (2014) and Olympic Games (2016). At that time, Rio de Janeiro experienced one of the largest waves of evictions in its history, with 20,000 families (over 80,000 people) evicted from their homes, the majority relegated to city’s extreme outskirts. Meanwhile in the wealthy South Zone, residents of some favelas received a title for their land in this same period of real estate boom and a wave of gentrification followed. There were even residents fighting against land titling because of the danger of “white eviction,” or gentrification.

The search for new land titling alternatives to strengthen housing security in the favelas and promote resident-led community development has proven urgent and essential. At the time, during a series of events organized by residents of the gentrification-hit favela of Vidigal, the idea of retrofitting the Community Land Trust model to favelas as a potential solution was discussed. However, it was only after the 2016 Olympics that those involved learned of CLTs’ real-world application in the favelas of Puerto Rico. In that context, the instrument was able to ensure the permanent status of communities, protecting their history and achievements while developing urban infrastructure on site, residents enjoying the benefits that come with these developments. When the tool was introduced in Brazil, it was given the Portuguese name Termo Territorial Coletivo (Community Land Trust).

“In and of themselves, there is nothing objectively negative about favelas: they are self-established, self-managed communities created to provide housing, trying to solve social issues in the absence of government, despite the absence of public investment.” — Theresa Williamson

Participatory territorial planning activity by the F-CLT Project in the Trapicheiros community in the North Zone of Rio.

Achieving a sustainable community requires a balance between ensuring tenure security for those who feel they belong, ensuring urban infrastructure to improve their quality of life, and guaranteeing the autonomy of residents over decision-making.

The event continued with presentations by other technical allies who have experience with the implementation of Community Land Trusts or other collective land management approaches in different contexts.

Lyvia Rodrigues, co-founder of El-Enjambre, shared the experience of the Fideicomiso de la Tierra Caño Martín Peña, the Community Land Trust established in the Caño Martín Peña community in San Juan, capital of Puerto Rico. Their CLT arose from two objectives: to regularize land ownership and enable the implementation of a comprehensive development plan for the region.

The Puerto Rican project faced many challenges during the process of building the CLT. As Rodrigues highlights: “In the context of Puerto Rico, where individual ownership prevails, establishing something different from that is a big challenge, not only in regard to dealing with external actors like the State, but [also] within the community itself. Beyond the difficulties experienced with regard to the government, residents showed a desire for the continuity of the organization to pursue the fulfillment of the community’s goals.”

Next, Juan Blanco—a Brazilian environmental manager working in sustainable urban planning and agroecology, cultural producer, and writer—shared his experience working as Executive Director of the San Francisco Community Land Trust in California. The main difference between the application of the model in Brazil and San Francisco is related to context. In San Francisco, as is typical with ‘traditional’ CLTs in the Global North, the CLT operates through the acquisition of buildings listed for sale and renting out units at an affordable rate. Meanwhile in Brazil, we work with self-built settlements that are struggling to have their land rights recognized.

Blanco nonetheless identified similarities between the two, especially related to the challenges surrounding realizing the right to housing. As one of the wealthiest cities in the US, San Francisco faces serious difficulties in providing low-income housing. The city has a significant number of people living on the streets, and a large part of the population that spends most of their income on rent, preventing them from meeting other needs. Similar processes are seen in the large Brazilian metropolises, where the high cost of living is a major obstacle preventing access to decent housing.

Blanco presented an alarming comparison to help Brazilians understand the scale of San Francisco’s housing challenges: “San Francisco is a city that has approximately 875,000 inhabitants, with 10% living below the poverty line. In January 2019, 8,000 people were living on the streets. For comparison, we have 12.3 million people in São Paulo and 42,000 people living on the streets. If São Paulo had the same proportion of homeless people as San Francisco it would be almost triple.”

Next, Yves Cabanes—a professor at University College London who was technical advisor on the Mutirão 50 Project in the 1990s—discussed this pioneering experience of collective urban land ownership in Brazil. Mutirão 50 was an initiative in Fortaleza, capital of Ceará state, and focused on the social production of housing through collective action, with a high degree of participation from residents.

At the time, cooperatives in Uruguay and Mexico were gaining strength, which was inspiring for the professionals and community leaders involved with the initiative. It was decided they would work with the same system and build a new area through collective action task forces and community participation. According to Cabanes, the project went far beyond the issue of housing itself by viewing the community through a holistic lens: “The idea was to build parts of the city in a collective way, and not just housing. Housing was a vehicle for achieving something else and to provide the equipment the community wanted, children at home while the mothers worked, a set of elements not only to build but to enable a relationship with the neighborhood.”

Entrance to the Mutirão 50 Project in Fortaleza, capital of Ceará, in the 1990s. Photo: Yves Cabanes Archive

Session 2: Presentations by Community Leaders who Experience Collective Land Management on a Daily Basis

In the second session we heard from community organizers involved with the projects who expressed their experiences with collective land management and its day-to-day challenges. We had the chance to hear leaders in Puerto Rico and Brazil.

The first to speak were Mario Núñez, executive director of the Fideicomiso de la Tierra Caño Martín Peña, and Lucy Riviera, president of the G-8, the community organization that manages the complex of eight favelas in Caño Martín Peña. They shared their experiences as residents of the communities that make up the Caño Martín Peña complex, which are bordered by a canal and are located in a strategic, highly valued location in the city. Settlement within the area began in the early 1900s. By the 2000s, the communities were long established in the area.

G-8 is a community organization made up of elected representatives from each of the eight communities that form the complex along the Martín Peña canal. They are a part of the G-8’s governing body and responsible for advocating for the needs of their community. At the time of the CLT’s formation, a local plan was established that involved community participation to coordinate with all of the community’s initiatives and create specific goals defined by the residents. Some of these goals included building community gardens, adult literacy programs, school garden, and a youth group, among others.

The implementation of the CLT was a strategy to avoid both the eviction of residents and gentrification of communities following the execution of the development plan, which on the one hand would require the resettlement of some families and on the other hand, when completed, would raise the value of land and thus make the permanence of the original families unviable. According to Núñez: “The CLT is permanent, established to manage the land, both occupied but also empty land that will allow for new housing. With the CLT they became landowners. As a result of Act 489 by the government of Puerto Rico on September 24, 2004, land in the north and south of the community was passed to the CLT.”

Riviera reflects on the performance of the CLT within the community and the feeling shared by residents of “love for the land, because they have been living here for many years, defending it tooth and nail. From an individual right, it becomes a collective right. Structures return; in those spaces we gather those living nearby to decide what they want [to put] in those spaces [by offering some] a temporary contract [for their use]. That way we ensure that [vacant land and spaces] are not underutilized. We received land, not money. We need to figure out how to keep growing.”

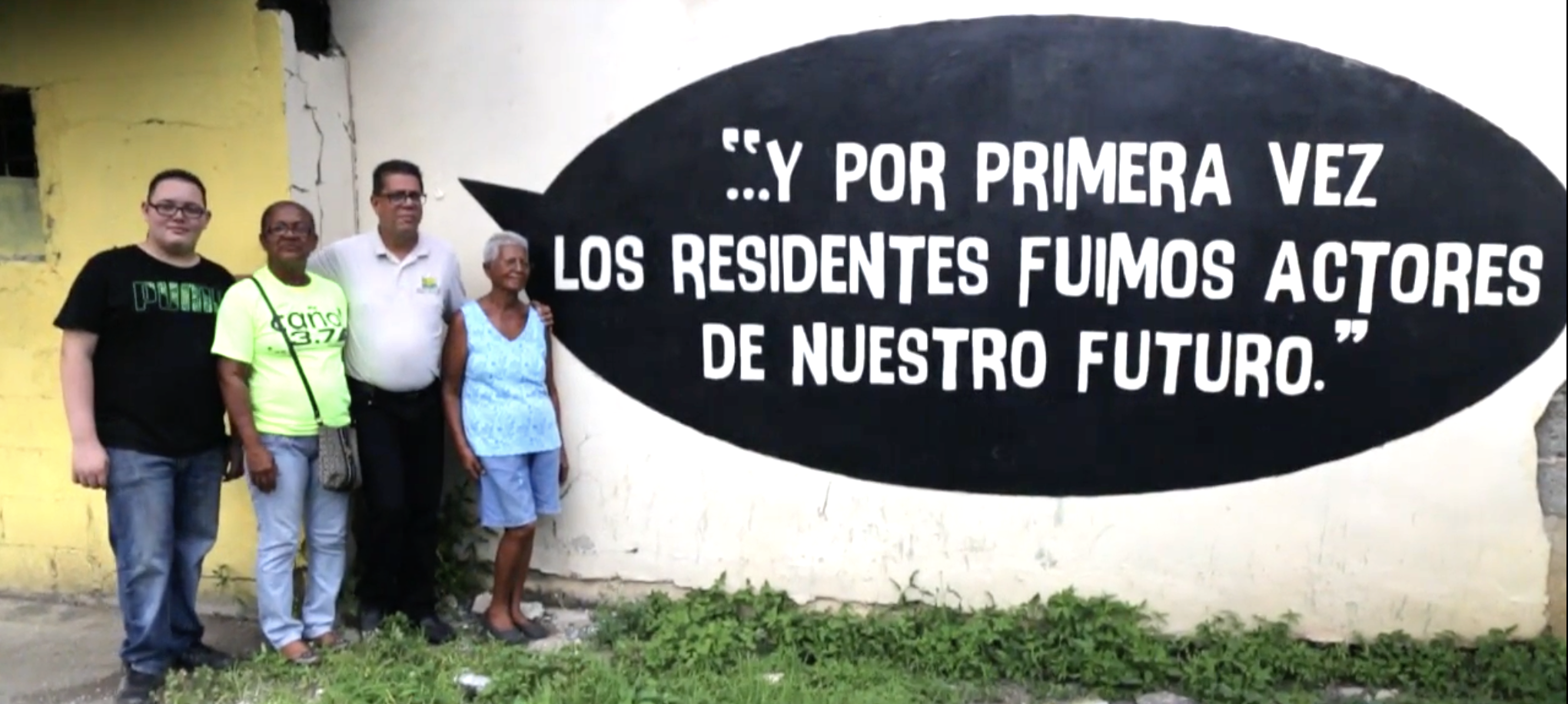

“…And for the first time, the residents were the authors of our future.” Members of the Caño Martín Peña CLT in front of a mural in the community.

Currently, the CLT has delivered 141 surface rights deeds to the residents of Caño Martín Peña’s eight communities. Many more are in the works. These documents guarantee official recognition that residents own their homes. Besides issuing land titles, the CLT carries out activities for the whole community, such as community tourism, recycling, income generation, cultural events, and more. Even residents who have not joined the CLT benefit from the infrastructure and community development projects.

Lastly, it was the turn of Rio de Janeiro’s Maria da Penha to speak—resident of the Vila Autódromo community, co-founder of the Evictions Museum, and known for her deep commitment to the struggle for the right to housing and to the city. She told us about her life story in the community where she lives, Vila Autódromo, which has suffered eviction attempts since 1992, putting its residents in a situation of permanent vulnerability and insecurity. Due to the community’s fight, government agencies were compelled to deliver concession of use titles to residents, recognizing the history of the community and the right to the land. Even so, this title was not enough to guarantee the survival of the community in the face of pre-Olympic speculative power games.

Between 2012 and 2016, purportedly “for” the Olympic Games to be held Rio de Janeiro, the City carried out a series of works for the construction of the Olympic Park. Although the land occupied by Vila Autódromo did not prevent the construction of the park, it was next door, thus the speculative pressures intense. Of 700 families, only 20 managed to resist eviction by the City and continue living there, and they are still fighting today for new ways to ensure their permanent status.

Maria da Penha reflected on her expectations for the implementation of the CLT: “The CLT shows how important collectivity is, the unity of residents. It brings a set of conditions whereby residents begin to understand the importance of their community, their land, the importance of being united and democratic.” According to her, the Community Land Trust seeks to unite the community in favor of the collective, so that residents start to see not only their individual needs, but also the needs of the community in which they live.

At the end of the event, panelists took audience questions. Participants expressed interest in better understanding the CLT tool and its possible applications in different environments and situations.

The webinar New Paths for Building Sustainable Cities: The Potential of Collective Land Management Based on the Community Land Trust raised important lessons with regard to thinking about community-developed solutions for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. It shows that the construction of sustainable cities must observe the practices already carried out in communities by and for residents. The event also sought to contribute to the wider spread of the CLT, reaching new audiences.

As an international event with live interpretation, the conference provided a broader outreach to international partners and the opportunity to connect with people from many countries who are interested in the CLT model and community practices developed in the Global South.