At 1st Sustainable Favela Network International Exchange, 5 Nations Light a Path to Climate Justice

On August 28, 2021, 258 people from 33 countries gathered online to participate our the first Sustainable Favela Network International Exchange, where twenty community organizers from informal settlements and underserved communities in five countries—Brazil, Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa and the US—presented their grassroots solutions to a range of socio-environmental challenges. The rich exchange was enabled by simultaneous translation between Portuguese and English by students from PUC-Rio‘s Interpreter Training Program. Participants joined the Zoom event at 10am for the opening of the first session, in which nine of the grassroots organizers were given the floor to present their community projects and the main socio-environmental challenges they have been facing. Two further sessions deepened reflection and bonding.

Quick introductions were made by Executive Director of Catalytic Communities (CatComm) Theresa Williamson, Pratt University professor Leonel Ponce, and two of the SFN’s facilitators, Iamê de Sá and Igor Valamiel.

Mauro Pereira, co-founder of an organization set up to defend the Serra do Mendanha mountain in Rio de Janeiro’s West Zone, Defenders of the Planet, moderated the first session, inviting each speaker to take the mic: Luis Cassiano Silva, creator of Green Roof Favela, in Rio’s Parque Arará favela; Monica Lewis-Patrick, founder of We the People of Detroit; Brian Otieno, member of the Mathare Social Justice Centre, in Nairobi, Kenya; Otávio Alves Barros, president of the Vale Encantado Cooperative; Dariella Rodriguez, Director of Community Development at The Point CDC, in The Bronx, New York; Jane Anyango, founder of the Polycom Development Project, in Nairobi, Kenya; Márcia Souza, director of the Favela Museum, in the Cantagalo favela of Rio de Janeiro; Michael Uwemedimo, director of the Human City Project and presenting Chicoco Radio from Port Harcourt, Nigeria; and, finally, Rose Molokoane, of Slum Dwellers International and resident of Oukasie, in Pretoria, South Africa.

Welcome: “We Are Actually Living a Dream”

Theresa Williamson, Executive Director of Catalytic Communities, first welcomed participants and shared her delight in seeing this unprecedented exchange happen which, thanks to it being online, enabled the presence of people from 33 countries.

Leonel Ponce then briefly introduced himself and described the power of such exchanges, this one following others he had organized bringing Pratt students to Rio de Janeiro and later grassroots leaders from Rio in New York for the 2019 Planner’s Network conference.

Iamê de Sá, facilitator of the Sustainable Favela Network’s Environmental Education Working Group, detailed how, since the network was first mapped online in 2017, many exchanges happened in 2018 and 2019 across Rio de Janeiro’s favelas permitting community leaders to learn from each other at the local level. In 2019, seven SFN working groups were launched, which later conducted actions in support of favela residents during the pandemic in 2020.

Igor Valamiel, facilitator of the SFN’s Memory and Culture Working Group, summarized the event agenda: a first session would be dedicated to community leaders presenting their projects, followed by a facilitated discussion in the second session. And, finally, a third session would invite speakers and the public to share cultural and emotive reflections.

Mauro Pereira moderated the first session introducing his work in implementing the 2030 UN Agenda, strengthening family agriculture, empowering youth, and influencing public policy. Pereira invited the first guest of the day to take the floor.

Building a Green Roof to Reduce Temperatures

Luis Cassiano Silva lives in the Parque Arará favela, in Rio de Janeiro’s North Zone. He works in theatre, audio-visual arts and is a cultural producer who also runs educational and socio-environmental projects. According to Silva, lack of space in Parque Arará is critical. Without room to plant trees or grow gardens, and in the face of high electricity prices, temperatures quickly rise to unbearable levels in his favela. Cassiano therefore built a green roof on his house, which he also displayed as a place to cultivate food: “I had this initiative to make a green roof to diminish the temperature inside my house. And it worked.”

He shared his concern that favelas will become increasingly hotter in the future and the urgent need to think of solutions. He is now thinking about establishing partnerships for a new project when the pandemic is over, with the objective of minimizing the overheating of water tanks in favelas during the summer. Silva finally shared his desire to expand such thinking: “I think it has everything to do with raising awareness, so that we can envision a better, more sustainable, and beautiful life.”

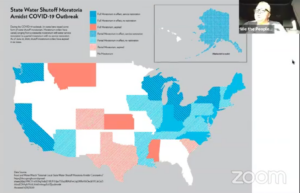

Advocating for Access to Safe and Affordable Water

Scholar, educator, entrepreneur, and human rights activist Monica Lewis-Patrick (also known as The Water Warrior) is the founder of We the People of Detroit (WPD), a community organization that addresses the water crisis in Michigan and around the world. Firstly, Lewis-Patrick mentioned how her small NGO was born out of the evidence of water shutoffs for a significant number of households in Detroit: “In the US, on average, 15 million Americans struggle to have access to clean, safe and affordable water,” she said. Lewis-Patrick presented a series of maps designed by her organization showing the link between the lack of water and the spread of diseases such as hepatitis A and coronavirus.

Scholar, educator, entrepreneur, and human rights activist Monica Lewis-Patrick (also known as The Water Warrior) is the founder of We the People of Detroit (WPD), a community organization that addresses the water crisis in Michigan and around the world. Firstly, Lewis-Patrick mentioned how her small NGO was born out of the evidence of water shutoffs for a significant number of households in Detroit: “In the US, on average, 15 million Americans struggle to have access to clean, safe and affordable water,” she said. Lewis-Patrick presented a series of maps designed by her organization showing the link between the lack of water and the spread of diseases such as hepatitis A and coronavirus.

Lewis-Patrick also denounced the government’s failure to address the water crisis in Detroit, the large hikes in water prices and the racist implementation of emergency management: “What we know is not only climate change, but structural violence based on racism is also creating some of these climate harms that are playing out in our communities. But we had to demonstrate to our own community, our own government that they were harming us by denying us access to an infrastructure that the residents of Detroit had built.”

Lewis-Patrick also denounced the government’s failure to address the water crisis in Detroit, the large hikes in water prices and the racist implementation of emergency management: “What we know is not only climate change, but structural violence based on racism is also creating some of these climate harms that are playing out in our communities. But we had to demonstrate to our own community, our own government that they were harming us by denying us access to an infrastructure that the residents of Detroit had built.”

Pereira replied by drawing a parallel with water access in Rio’s West Zone: “We produce water in our massifs, in our state parks of Pedra Branca and Mendanha, but our communities continue to suffer greatly from lack of water and basic sanitation,” and congratulated her on her actions.

The Environmental and Social Impacts of Tree Planting

Brian Otieno, a Kenyan artist, activist, and scholar, born and raised in Mathare, the second largest informal settlement in Nairobi, is a member of the Mathare Social Justice Centre and coordinator of the Art for Social Change Campaign. He is also a defender of ecological justice, dedicated to planting trees within his neighborhood. “If you want to make a change, you have to dig a hole, plant a tree,” he said. Known by the artistic name of Stoneface Bombaa, he talked about the injustice in Mathare, but also of the frequent massacres the community has been facing. By planting trees, he explains, his community can not only have an environmental impact, but also a social one: “By planting these trees, we bring back the memories of the people gunned down by police brutality that has been taking place in our community every now and then. We name those trees after the people that were shot down by police officers.” Their goal: to plant 10,000 trees in the community within the next five years.

A Favela Biodigester Transforms Sewage into Cooking Biogas

The next presentation was given by Otávio Barros, president of the Vale Encantado Cooperative and Residents’ Association. The community’s cooperative engages local families in initiatives developing the community as a sustainable model. Their accomplishments include a unique local cuisine, solar water heating, a food waste biodigester, and a sewage biosystem including a biodigester that produces biogas used by the community.

Barros, whose family has been living there for five generations, presented the projects currently being developed by the Vale Encantado community. He explained how the cooperative kitchen’s biodigester works: food waste is placed in the biodigester where it is digested by microorganisms that produce biofertilizer and gas, which then returns to the cooperative’s kitchen, to produce and bake goods to be sold at the community restaurant.

The community has also built a sewage treatment biosystem that depends, in part, on a root zone filter and that is so far connected to five houses. “This improved not only the quality of life of residents, but also the environment. It has already helped the quality of the water that is thrown in our river… The sewage treatment system is maybe a first reference among Rio de Janeiro’s favelas, for it is carried out and sustainable within the community.” Barros pointed out that the solutions found for Vale Encantado came from within the community and through a lot of hard work, and that the local government is uninterested in the wellbeing of many communities, particularly those as small as his.

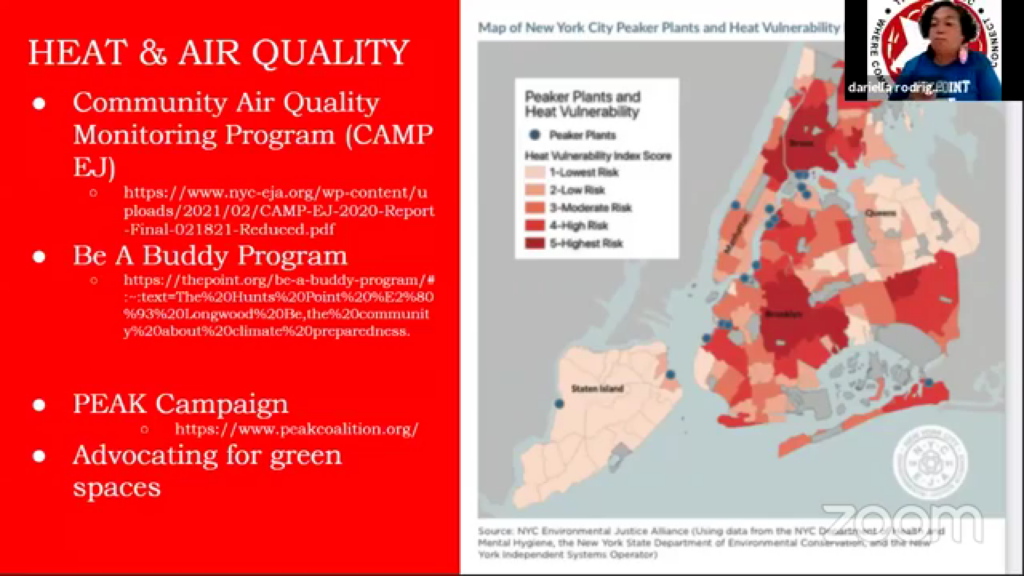

Responding to Basic Needs and Emergency Preparedness

Dariella Rodriguez, a New York-based community organizer, works on campaigns addressing environmental justice, notably food justice, and education reforms. Her organization, The Point, was founded 25 years ago when Rodriguez’s community realized that there was a need for young people to engage in art programs that could bring their culture into their everyday lives, and through which issues impacting their communities could be addressed. She recalls:

Dariella Rodriguez, a New York-based community organizer, works on campaigns addressing environmental justice, notably food justice, and education reforms. Her organization, The Point, was founded 25 years ago when Rodriguez’s community realized that there was a need for young people to engage in art programs that could bring their culture into their everyday lives, and through which issues impacting their communities could be addressed. She recalls:

“There was this story of the Bronx, that you needed to escape as fast as you can if you wanted to be a successful person. The Point became a testament to what community members were able to do when they saw themselves as the greatest asset that our community had and brought their skills, their talent, and their culture to a shared space.”

Rodriguez sees her community as being a “sacrifice zone” to public authorities: the problems faced are very basic, such as air quality or heat, but they could easily be linked to the lack of investment in the area’s infrastructure. She also mentioned partnerships with artists “not only to create murals and public art, but also to see how we can be intentional about dreaming of a different future.”

Rodriguez sees her community as being a “sacrifice zone” to public authorities: the problems faced are very basic, such as air quality or heat, but they could easily be linked to the lack of investment in the area’s infrastructure. She also mentioned partnerships with artists “not only to create murals and public art, but also to see how we can be intentional about dreaming of a different future.”

Empowering Women in Kibera, Kenya

The sixth community leader to speak was Jane Anyango, a Kenyan activist for peace and women and girls’ rights. Founder and director of the female empowerment Polycom Development Project, that intervenes in both schools and informal settlements, she explained how women mobilized in 2007 and 2013 to respond to post-election violence in a country divided among over 42 tribes.

The sixth community leader to speak was Jane Anyango, a Kenyan activist for peace and women and girls’ rights. Founder and director of the female empowerment Polycom Development Project, that intervenes in both schools and informal settlements, she explained how women mobilized in 2007 and 2013 to respond to post-election violence in a country divided among over 42 tribes.

Anyango then presented various projects and activities implemented by the organization at the school level, especially to address sexual harassment. One of them is called Talking Boxes:

“We install boxes in schools, we lock them up, and we encourage children to put in anything they want to share, mostly the problems they face in their homes, their community and everywhere. Then we organize forums to address the issues that they face.”

She went on to explain how this enabled them to elaborate ground-breaking programs on girls’ harassment, also noting that there is no definition of sexual harassment in Kenya. Still focusing on women’s empowerment, the organization further launched events on urban farming, and public participation and accountability, always specifically designed for women.

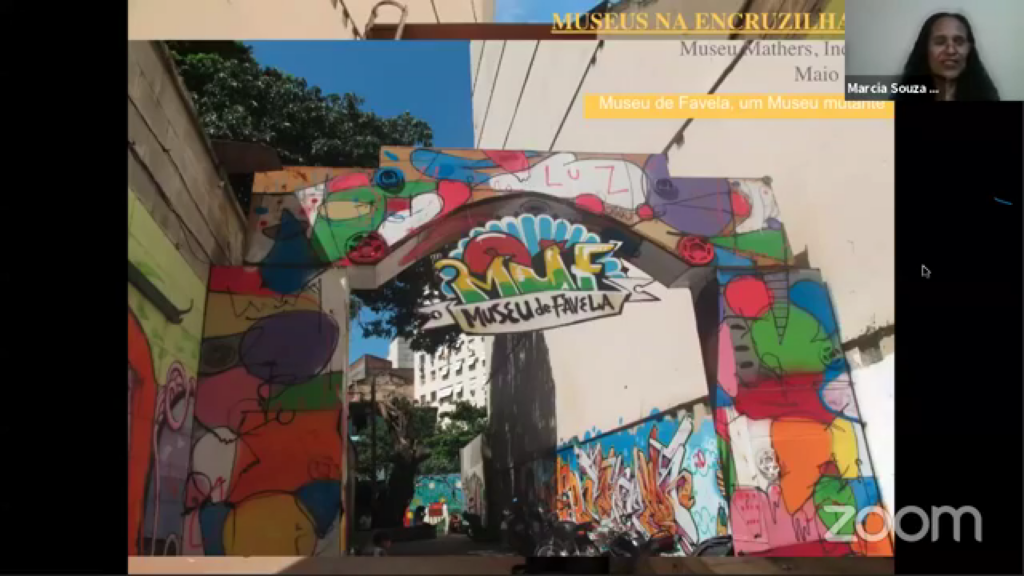

“The Collection Would Be The People, the Favela is the Museum”

Márcia Souza, a resident of Cantagalo, a favela in Rio’s South Zone, is a social activist and event producer, as well as a territorial mediator. She has been a member of the Sustainable Favela Network since its beginning and presented the project that she co-founded and currently directs: the Favela Museum. Created in 2008 in Cantagalo, it marks a new era in museology. Cantagalo is located between two of Rio’s wealthiest neighborhoods, and its most popular among tourists: Ipanema and Copacabana. Community residents could sense the desire of tourists staying in these areas to come up and visit the favela. Collectively, a group of residents thought of ways to create sustainable tours that reinforced the community as a critical part of the city despite chronic neglect from government. The open-air Favela Museum was born: “the collection would be the people, the favela is the museum.”

“As we listened to people’s stories […] we started implementing the museum. This museum tells its story through the art, the culture, the samba, the music. We captured the knowledge of the favela and started to share it, receiving visitors.”

Chicoco: A Youth-Empowering Nest of Creativity in Port Harcourt

Michael Uwemedimo is a law graduate, co-founder and director of the Collaborative Media Advocacy Platform, as well as project director of the Human City Project, on which he focused his presentation. The project is based in Port Harcourt, the oil capital of Nigeria, and consists of a community-driven media, architecture, planning, and human rights initiative. Uwemedimo mentioned the important environmental degradation of this neighborhood due to hydrocarbon extraction, which impacted water and soil. Another major problem is that of safety due to the demolition of settlements. The Human City Project was created as a space for people to be seen and heard and thus were created: Chicoco Radio, sharing the music and stories of the communities; Chicoco Studios, where people make and play music; plus, Chicoco Cinema, Chicoco Maps, and Chicoco Shed. All these facilities are currently being gathered under a single roof called Chicoco Space.

Michael Uwemedimo is a law graduate, co-founder and director of the Collaborative Media Advocacy Platform, as well as project director of the Human City Project, on which he focused his presentation. The project is based in Port Harcourt, the oil capital of Nigeria, and consists of a community-driven media, architecture, planning, and human rights initiative. Uwemedimo mentioned the important environmental degradation of this neighborhood due to hydrocarbon extraction, which impacted water and soil. Another major problem is that of safety due to the demolition of settlements. The Human City Project was created as a space for people to be seen and heard and thus were created: Chicoco Radio, sharing the music and stories of the communities; Chicoco Studios, where people make and play music; plus, Chicoco Cinema, Chicoco Maps, and Chicoco Shed. All these facilities are currently being gathered under a single roof called Chicoco Space.

“We Have to Come Together As The People”

Rose Molokoane was the last guest to present in the first session of the first Sustainable Favela Network exchange. A resident and member of the Oukasie savings scheme in an informal settlement outside Pretoria, South Africa, she moved the audience with her statements, such as:

“We have to come together as the people, so we can show this world that we are not just recipients of leftovers of policies, but that we can become the decision-makers when it comes to formulation of policies and the implementation of policies.”

The globally known grassroots activist, involved in housing and tenure issues, presented the Slum Dwellers International (SDI) network that brings together grassroots leaders from informal settlements across the Global South. The aim of the organization is to lead governments to enact slum-friendly policies. She explained how the organization looks at women in vulnerable situations and works to implement women-centered transformations of communities and cities, while also promoting youth mobilization and media work. According to her, community organizing comes first, and from it partnerships with government can happen.

Following Molokoane’s presentation, Mauro Pereira concluded the session by affirming the need for global action. For him, the Sustainable Development Goals must be applied universally while guaranteeing local impact, “without leaving anyone behind.”

Watch the First Session of the 1st Sustainable Favela Network International Exchange:

A Facilitated Discussion Across Borders

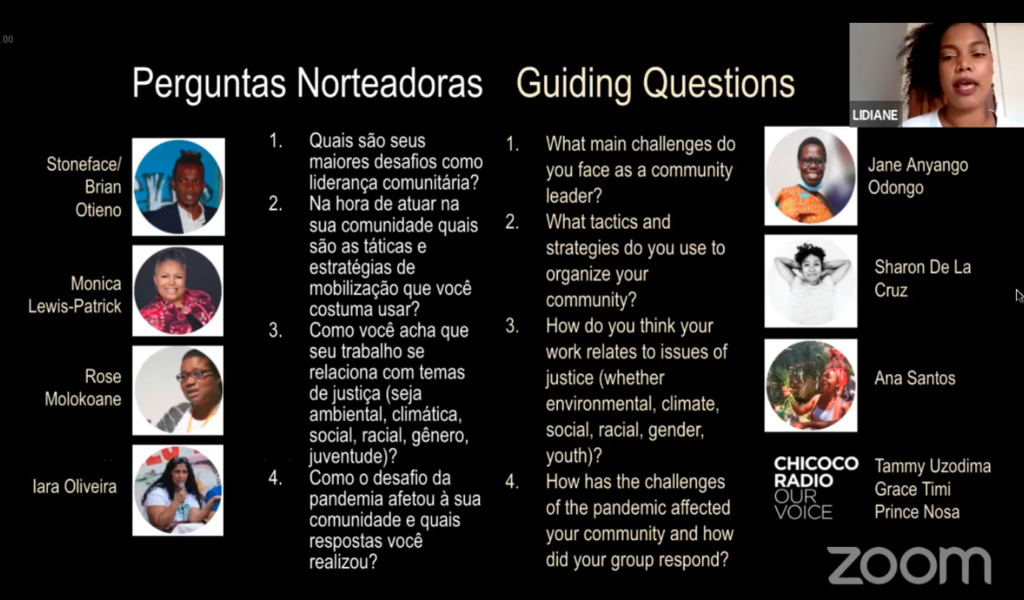

The event’s second session was run as a facilitated discussion between community organizers from informal settlements and other underserved communities in five nations, followed by the third session: an emotive cultural exchange. Four questions were prepared asking each participant to describe their political and cultural contexts, challenges, organizing tactics, responses to the pandemic, and how their work relates to issues of social justice.

The session’s facilitator was Lidiane Santos, from the community organization Alfazendo, based in the favela of City of God in Rio de Janeiro. Participating in the conversation were: Brian Otieno, also known by his artistic name of Stoneface Bombaa, member of the Mathare Social Justice Centre in Kenya; Jane Anyango, Kenyan activist and founder of the Polycom Development Project; Sharon De La Cruz, director of sustainability at The Point CDC, in the Bronx, New York; Iara Oliveira, founder and coordinator of Alfazendo; Prince Nosa and Grace Timi, from Chicoco Radio, in Port Harcourt, Nigeria; Rose Molokoane, coordinator of the South African Federation of the Urban Poor (FEDUP) and member of the Management Committee of Slum Dwellers International (SDI); and Ana Santos, educator from the Center for Multicultural Education (CEM) in the favelas of Complexo da Penha, Rio de Janeiro.

What main challenges do you face as a community leader?

The first question was about the challenges each faces as a community leader. Stoneface Bombaa began by describing problems faced with the police in his community of Mathare, the second largest informal settlement in Nairobi. Stoneface described how police block and hold back local actions. Jane Anyango, also from Nairobi, described conditions in Kibera, the largest informal settlement there, where she works. She described the difficulties of her work, having become a reference for women who “look up to us as a source of hope.” She personally feels sad, and the women she supports lost, when she cannot help them. “Sometimes we don’t have enough resources to help. We don’t get enough support from the government, even though we work a lot for the communities,” said Anyango.

Of the Bronx, in New York, De La Cruz responded to the same question by highlighting that “one of the main challenges exacerbated by the pandemic is the community organizing process. We all may have the greatest of intentions, but what does your process look like? [We should] think about how the process can be as inclusive as possible. Taking into account design processes that, if there is a point of contention or disagreement, can address them without things getting personal.”

What tactics and strategies do you use to organize your community?

The second question posed was on the tactics and strategies that each leader uses to organize and mobilize their community. Iara Oliveira shared that, in Alfazendo, they have learned that listening and respecting everyone is the best strategy to deal with people and to fight for rights in a participatory environment. Prince Nosa and Grace Timi said that they first try to understand what the community needs, and only then do they start planning. As a community they “use a map and we put ourselves on it to say where we come from. And this tends to tell us stories. And from these stories we start to plan,” said Nosa.

Anyango stated that, in her organization, they always try to align the work they do with existing frameworks, such as the Sustainable Development Goals and the New Urban Agenda. “We also do a lot of advocacy at a community level and often collaborate with people that sympathize with the cause. We use a lot of local agents and try to make people talk a lot, so we can resonate their voices. We do a lot of lectures on the radio, show films, and pictures as well,” said Anyango.

How does your work relate to issues of justice?

How each one’s work related to issues of justice (environmental, climate, social, racial, gender, youth) was the third question asked. Ana Santos of Rio’s Center for Multicultural Integration listed the twin problems of food and climate justice, to which she and her colleagues respond by pursuing food sovereignty, water, proper housing, and agroecology. “Were it not for the By Us, For Us way of doing things, we would be much weaker in this society. This event makes me much stronger, I feel like I’m part of a much bigger network. The work is local, but the articulation is global,” said Santos. Molokoane of Slum Dwellers International also answered that they struggle a lot with land and services in South Africa, facing evictions and social violations from the government.

She added: “If we get people their rights, moral and financial support, we can work together and change problems. We need to make noise in a positive way. We need to plan for the long term, not just for the communities today. Women are not safe at all. Their children are not safe. Unemployment is huge. We are struggling to make things be done properly. If we don’t do it now, we will regret it later.”

How has the pandemic affected your community and how did your group respond?

The final question dealt with the challenges faced by their communities in responding to the pandemic. De La Cruz was the first to answer, saying that they noticed, in the Bronx, that the lack of Internet access in many homes was breaking with their children’s right to education. Ana Santos expressed that her community suffered with housing and lack of financial resources due to the government’s late response to the crisis, which resulted in people not having money to pay their rent and entering the drug traffic to earn money.

Iara Oliveira also contributed by saying that, currently, food security is a huge issue: “Without the work of grassroots organizations, a much larger number of people would have died. We were left alone, with a denialist president. With the pandemic, we started to distribute baskets of basic foodstuffs, which is not our usual objective. We were able to serve seven thousand people.” Molokoane closed the second session recounting that the pandemic blocked most of their projects, and that not being able to travel internationally harmed their movement.

Watch the Second Session of the 1st Sustainable Favela Network International Exchange:

Event Ends Amidst an Intimate, Emotive Cultural Exchange

After a quick break, the third and final session of the exchange began. Each organization and the public were encouraged to share cultural or philosophical elements to inspire resilience in one other. Songs, poems, readings and testimonies were exchanged in a more casual dynamic, facilitated by Bruno Almeida, professor, historian and general coordinator of the Historic Orientation and Research Nucleus of Santa Cruz (NOPH), the first community ecomuseum in Brazil, and member of the Sustainable Favela Network’s Memory and Culture Working Group.

The various exchanges moved the audience by bringing emotional speeches and inspirational art. Nill Santos, founder and coordinator of the Association of Assertive Women with Social Commitment (AMAC), in Duque de Caxias, Greater Rio, drew attention to the collective power raised that day: “We get tired, and we feel alone, but it’s amazing to see that we are here together, with the same struggles. It doesn’t matter the country. We are not alone. Do you know why? We are the energy that drives and sustains this planet. I am because we are. That is what drives us.”

She was followed by Zoraide Gomes, known as Cris dos Prazeres, who manifested her passion for nature and ecology with an hopeful speech, followed by Nosa and Timi sharing the video “Somebody’s Brother” produced by Chicoco Radio and exploring police violence:

De La Cruz showed a video of the children in her community singing All I Want for Christmas is You. Ana Santos, Maria Consuelo Pereira dos Santos, Julio Fessô, Thállita Sanches, and Lidiane Santos read original texts and poems, which, together with those of other members of the public, were shared on Padlet:

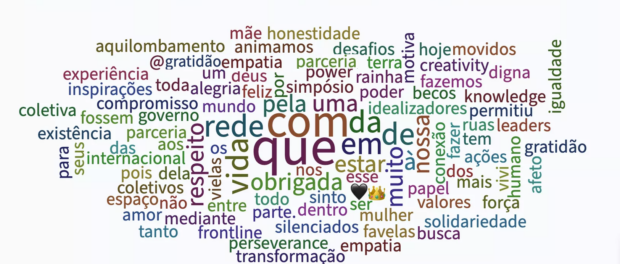

A “Cloud of Strength” was produced during the event and shared via Zoom, answering the question: what gives you strength in the struggle for socio-environmental justice?

The event ended with combined voices singing Rap da Felicidade (The Happiness Rap), a song that celebrates favelas, their sense of belonging, and a common wish for a better future across informal settlements: