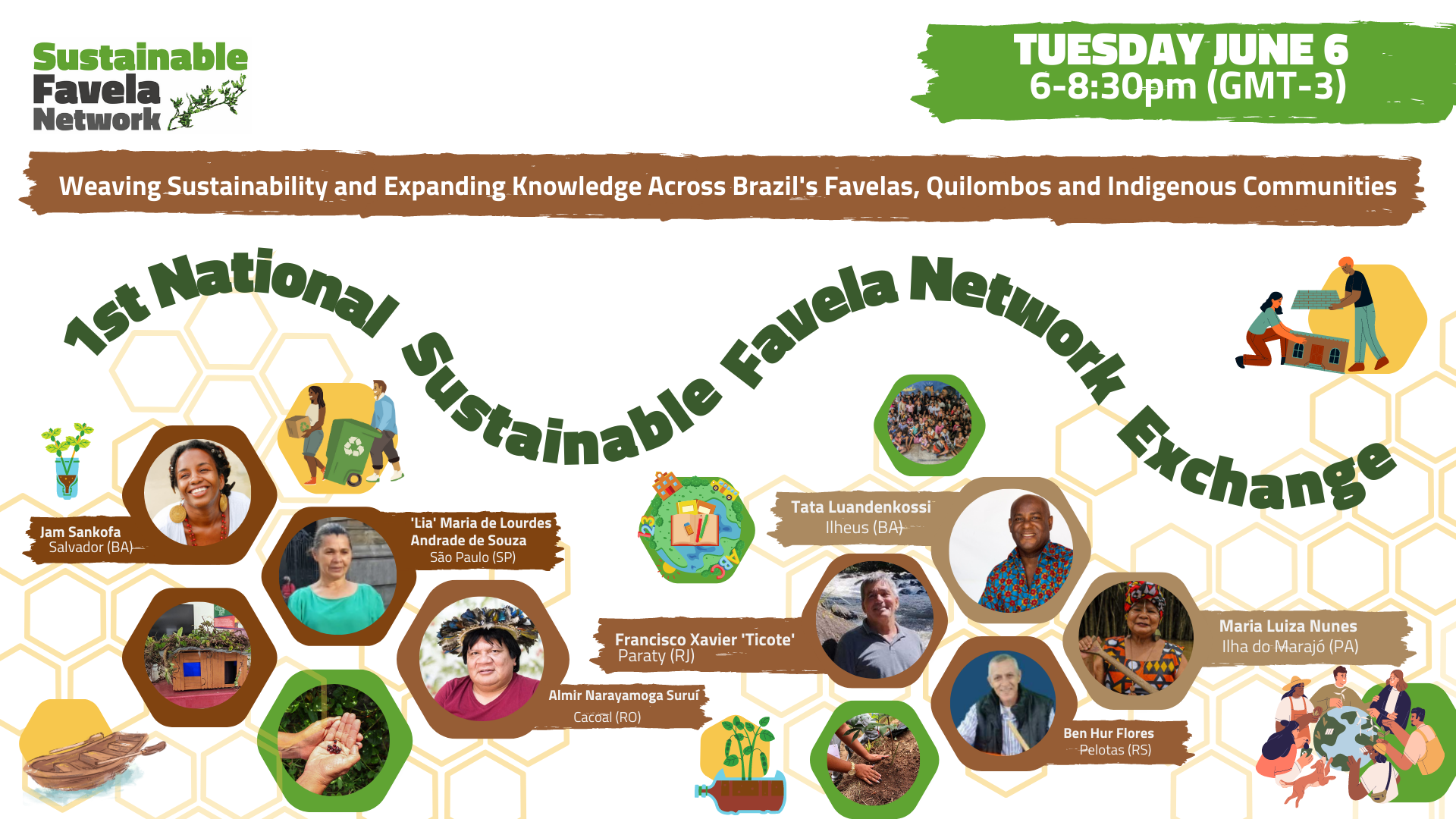

1st National Sustainable Favela Network Exchange Expands Knowledge and Weaves Sustainability Among Brazilian Favelas, Quilombos and Indigenous

1st National Sustainable Favela Network Exchange Expands Knowledge and Weaves Sustainability Between Favelas, Quilombos, and Indigenous Communities.

On June 6, 2023, 155 community organizers and allies from 12 Brazilian states—Bahia, Ceará, Mato Grosso do Sul, Minas Gerais, Pará, Pernambuco, Rio de Janeiro, Rio Grande do Norte, Rio Grande do Sul, Rondônia, Santa Catarina, and São Paulo—gathered online to participate in the First National Sustainable Favela Network Exchange: “Weaving Sustainability and Expanding Knowledge with Favelas, Quilombos and Indigenous Communities.” The event was attended by community organizers and residents who, in honor of World Environment Week, came together to address sustainability through their own voices and experiences.

The powerful exchange featured special guests from indigenous, quilombola, fishing, and favela communities across Brazil and was held in three sessions: introductions, debate, and a cultural exchange. The change in sessions sought to ensure moments for speaking, listening, and affection, between special guests and community organizers from Rio de Janeiro’s Sustainable Favela Network (SFN)*. The event started with a basic introduction to the SFN, which works along eleven thematic objectives: (1) climate justice, (2) socio-environmental education and research, (3) participatory policy-making, (4) local culture and memory, (5) food sovereignty, (6) collective health, (7) solidarity economy, (8) right to sanitation, (9) energy justice, (10) just transport, and (11) sustainable housing.

The exchange was built collectively by the SFN through six meetings with the involvement of many members. Exchanges are seen as the heart of the network and have the primary objective of providing spaces for the exchange of knowledge, support, and inspiration between different favelas and community organizers.

1st Session: Special Guest Introductions

Almir Narayamoga Suruí, Chief of the Paiter Suruí people in Cacoal, Rondônia, at the 1st National Sustainable Favela Network Exchange

Almir Narayamoga Suruí, from the Suruí Carbon Project and Sete de Setembro Indigenous Land in Cacoal, Rondônia, opened his talk by introducing himself and his people, their territory, their challenges, and their struggle.

“Our state is part of the Brazilian Amazon. We are here, occupying an area of 248,000 hectares of forest. The Paiter people, my people, are approximately 2,000. We are looking for answers to the great challenge ahead…, in 2000 coming up with strategies for the next 50 years of the Paiter Suruí people. From then on, we began to create sustainable development strategies within our territory, trying to show that it’s possible to develop economically and culturally alongside the forest… These criteria are not only defined by law but also by nature, the universe, and life—criteria that are quite broad. Climate change is here, a response to the world’s actions: aggressive deforestation with no justification… It is a challenge for us, even today, to work with this awareness in the medium and long term, so that we can guarantee the future of humanity, future generations, strengthening the economy, continuing to produce, respecting the environment, respecting life and also using technology… It is very important that we bring a balance and a fairer society. Unity with respect, with no exploitation, no prejudice, and no discrimination.” — Almir Narayamoga Suruí

Ben Hur Flores from the Angels and Cherubs Project in Pelotas, Rio Grande do Sul, at the 1st National Sustainable Favela Network Exchange

Ben Hur Flores from the Angels and Cherubs Project in Pelotas, Rio Grande do Sul, spoke about his project which involves art, education, and sustainability aimed at youth. In addition, he spoke of hope for a better future for subsequent generations.

“We created the Angels and Cherubs Project in 2001 because we lived in a community where violence was so common, so natural. Children lived with this violence and thought everything was fine. My children were growing up in this environment. So, I created a theater project… so that we could give them some occupation… I had no idea of the power art had to transform lives… The first generation [of the project] has youth going to university, others have already graduated and entered the job market, they have a family, and a house in the community. They are the transformers, those who will continue this change… In the meantime, we [have] received some recognition at the national and local level, but the recognition I value most is seeing youth who went on a first exchange trip in Complexo do Alemão, who saw that it is possible, that even if they are Black, poor, from the favela or urban periphery, they can achieve whatever they want.” — Ben Hur Flores

Jam Sankofa, an artist from Salvador, Bahia, at the 1st National Sustainable Favela Network Exchange

Jam Sankofa from the Afrociclos Network in Salvador, Bahia, recalled her educational background, references, and ancestry, and introduced her work with cycling and bicycles as a tool for autonomy and socio-environmental activism.

“I am a poet, singer, songwriter, artisan… I was born in the city of Salvador, in a neighborhood also called Quilombo Urbano de Pernambués… I come from the urban periphery community of Guiné… the bicycle kick-started something I think. It greatly transformed my journey beyond the hip hop movement, poetry, my experience with the street, with cultural production in the urban periphery… I learned to ride a bike at the age of 24; as I said, I come from a community in the urban periphery with various socioeconomic and structural vulnerabilities, and there was one bicycle [used by] the whole street, with no brakes… there was little access to this tool… As nothing is by chance, for us, who are connected with ancestry, everything has its ways. The following year, I met some girls who worked with cycling entrepreneurship and they invited me to be part of what would become the collective… We created a project where we taught women how to ride a bike… understanding the bicycle as a sustainable, healthy, autonomous transportation tool that gives us access to spaces.” — Jam Sankofa

Lia Esperança, community organizer from Vila Nova Esperança in São Paulo, at the 1st National Sustainable Favela Network Exchange

Maria de Lourdes Andrade de Souza, also known as Lia Esperança, started the Lia Esperança Institute and is a community leader from Vila Nova Esperança favela in the city of São Paulo. She spoke about her struggle against forced evictions and how her community became a model of socio-environmental organizing and food sovereignty.

“There was an eviction process because families lived in an environmental protection area… I started [to] fight alongside them and show that the courts cannot come [and evict] residents just because they are in an environmental protection area… saying they are degrading [the area]… I had the idea… [of] how to transform Vila Nova Esperança into a sustainable community. I didn’t and still don’t have a college degree, but I had the idea of making a vegetable garden and, through the garden bringing environmental education into the community… we here in Vila Nova Esperança learned to do things together; there’s no teacher and no student, we all learn from each other, each contributing our wisdom. We come together and transform spaces… Then we saw that the vegetable garden could also bring not just environmental education, but also food security into the community… with our vegetable garden, we brought health to our community.” — Maria de Lourdes Andrade de Souza, “Lia Esperança”

Maria Luiza Nunes, member of the Black Mothers of the Amazon Collective in Pará, at the 1st National Sustainable Favela Network Exchange

Maria Luiza Nunes, a member of the Black Mothers of the Amazon Collective and the Quilombo Boca da Mata on Marajó Island in the state of Pará, opened her talk by greeting her ancestors through prayer:

“I exist because someone before me existed

Because someone before me persisted

Because someone before me resisted

They planted and taught me to plant

They planted and taught me to plant.”

She then introduced herself, sharing knowledge inherited from the forest, as well as the importance of the political body of Black women in the defense of the Amazon and cultural resistance.

“I was born in the quilombo called Boca da Mata, in Salvaterra, on the island of Marajó, a place where production revolves in accordance with time, with respect for the sacred, considering that the sacred for us are the rivers, the forests, the igapós, the igarapés and all the production that comes from these places… My grandmother, whom we called Mother Maria or Mariazinha, [was] a bush artist, ceramist, seamstress. I come here proud of the knowledge inherited from these women… Recognizing that we are walking culture reconnects us with other Black women. So, in 2019 we created, together with a group of women, the Black Mothers of the Amazon, knowing that doing is political, but it is learning from our grandmothers, from our mothers, who long ago already practiced the economy of care, the economy of affection, the differences between gain, price, and value, and that this body is political, it is a political territory, so everything I do… is drenched in the knowledge, the inherited knowledge from these women and men who make up my territory… Cosmo-connectivity links us to our spaces, to our essences.” — Maria Luiza Nunes

Tata Luandenkossi from the Dilazenze Black Culture Preservation Group and Gongombira Culture and Citizenship Association in Ilhéus, south coast of Bahia, asked the elders for their blessing through song:

Tata Luandenkossi from the Dilazenze Black Culture Preservation Group and Gongombira Culture and Citizenship Association in Ilhéus, Bahia, at the 1st National Sustainable Favela Network Exchange

“Oh, grant me permission, oh

Oh, grant me permission

Oh, grant me permission, oh

Oh grant me permission

Alodê Yemanja, oh, grant me permission

Alodê Yemanja, oh, grant me permission..” — Tata Luandenkossi

He went on to emphasize the importance of memory, an ally of the environment and a great asset in the fight for public policies.

“I am Tata Luandenkossi, from the Matamba Tombenci Neto terreiro [a traditional temple for Afro-Brazilian religious and cultural practices], in Ilhéus, Bahia. It is located in the Conquista neighborhood, with nearly 20,000 inhabitants, mostly Black men and women… It is a century-old terreiro founded in 1885 by members of my bloodline, the Rodrigues family, and where the Gongombira Culture and Citizenship Organization is located today, and of which I am currently president. It is the institution responsible for promoting cultural policies within the Matamba Tombenci Neto terreiro… the terreiro [is like] a university of life for us… always with the endorsement of our Mother Ilza Mukalê, we have various projects related to education, heritage, and the environment.” — Tata Luandenkossi

Francisco Xavier Sobrinho, Ticote, from the Pouso da Cajaíba Residents Association in Paraty, Rio de Janeiro, at the 1st National Sustainable Favela Network Exchange

Francisco Xavier Sobrinho, known as Ticote, is from the Pouso da Cajaíba Residents’ Association in Paraty, in the Costa Verde region on the south coast of Rio de Janeiro state. In his presentation he shared the struggle for an education that respects local knowledge. He spoke with pride about the children in his area who are now able to study for longer in their community.

“I come from a caiçara [traditional fishing] community called Pouso da Cajaíba, here in Paraty, Rio de Janeiro. I come from a journey of struggle in my community for education… I transformed my house into the Caiçara Permaculture Institute (IPECA), an institute of caiçara education… We created the Traditional Communities Forum: indigenous, quilombola, and caiçara… We discuss ecological sanitation, differentiated education, community-based tourism, agroecology, and various other topics, including the fishing movement. So, we have several fronts of struggle in this context… Today, we have the Bocaina Observatory of Sustainable and Healthy Territories (OTSS), a partnership between the Traditional Communities Forum and Fiocruz.” — Francisco Xavier Sobrinho, “Ticote”

2nd Session: Open Debate

The second session of the event focused on a greater exchange between guests from all over Brazil and community organizers from the Sustainable Favela Network in Rio de Janeiro. For this, youth members of the SFN introduced a few questions to compose open debate circles on the themes of climate justice, sustainable housing, food sovereignty, and socio-environmental education.

In the debate circle on the theme of climate justice, Matheus Edson, born and raised in the Rio das Pedras in Rio’s West Zone, geographer and volunteer in two community college prep courses in the favela, commented: “We know that we are currently suffering a lot from climate change and we know that these impacts affect social groups differently, especially the most vulnerable.” With that, addressing the guests, he asked what each special guest and their group is doing within their community to contribute to the fight against global warming and for climate justice.

How Are You Contributing to the Fight Against Global Warming and for Climate Justice?

Almir Suruí answered that his people, the Paiter Surui, started in 2005:

“… reforesting the deforested area. We have already planted over one million seedlings and started producing sustainable agroforestry products like coffee, nuts, and cocoa. We are also involved in tourism… recognizing it can help with education, the economy, the environment, culture, technology, and management.”

In her response, Jam Sankofa highlighted the importance of racializing the issue of climate justice:

“We, from urban periphery communities, quilombolas, and communities that are socioeconomically most vulnerable, are the most affected by climate change… changes that we are not the ones causing… What is the development perspective of indigenous peoples? What is the development perspective of Black people? So, we look to this horizon to understand that our future does not align with predatory ideas. That’s why we promote active mobility, bicycles… understanding that education is a tool to preserve our culture… a culture that is also Afrocentric.”

David Amen, member of the Roots in Movement Institute from Complexo do Alemão, North Zone of Rio, shared his experience in the favela to add to the debate. He recalled the heavy rains that hit Alemão in 2003, a socio-environmental disaster that impacted the lives of his neighbors. He said that they currently seek solutions through local organizing by stimulating debates:

“We do a lot of research and have a very strong partnership with social organizations across Complexo do Alemão. In this specific case, NGOs that work on recovery, environmental education, with the environment in general. This has led to closer relationships and dialogues so we can find plausible solutions for the environment, for climate justice… [including] a Popular Action Plan for Complexo do Alemão with various social proposals, solutions to problems, including in the environmental area.”

What Does Sustainable Housing Mean to You?

On posing the question ‘what does sustainable housing mean to you?’ Lia Esperança emphasized that living with respect for nature is essential.

“We do everything to have a place to live, but also to not harm our environment, because we have to have our home and also have a way to live with nature without harming it. And that’s what we do here. We now have a vegetable garden, we also have our kitchen. Everything we build here, we build without taking down trees, we build together with the trees.” — Maria de Lourdes Andrade de Souza, “Lia Esperança”

Tata Luandenkossi shared the experience of the Matamba Tombenci Neto Cultural Complex, an urban quilombo with several families living in it. Through a lot of dialogue and collective organization, they managed to make improvements in the quilombo’s housing.

“Every year we hold a meeting to evaluate what we have achieved and what we still need to achieve. This is how we managed to solve open sewage problems and the issue of piped water; we also managed to solve problems related to the physical structure of houses. We built a square within our space, based on this listening… Today, we have a memory space within our community, which is the Unzó Tombenci Neto Memorial.” — Tata Luandenkossi

Anna Paula Sales from Itaguaí, a municipality in Greater Rio, is a leader from the Itaguaí Women’s Association—Warriors and Social Articulators (A.M.I.G.A.S.) and founder of the Itaguaí Solidarity Kitchen. She shared a happy memory of her youth at the Sepetiba Bay, where rain was synonymous with joy: “when it rained it was great, everyone went out in the rain on the beach. It was a really picturesque, pleasant thing. Playing in the rain was a celebration.” But now the situation is radically different, with heavy rains, vulnerability of housing in the area, and lack of public investment:

“After 40 years, the rain that brought us so much joy is now synonymous with a nightmare, with terror. How can you not be worried about half an hour of rain in any favela in the state of Rio de Janeiro or in Brazil?”

Zoraide Gomes, known as Cris dos Prazeres, from Morro dos Prazeres, a favela in Rio’s Central Santa Teresa neighborhood, also shared a memory of fear when she spoke about the rains and housing. She recalled the tragedy that occurred in the favela in 2010, when 35 people died and many others were left homeless after a hillside collapsed following heavy rains. After that incident, the community began to organize and seek solutions given the government’s absence in relation to solid waste management, responsible for the collapse.

“Prazeres began to think about how to dispose of [its solid waste] in a correct way, how to take care of this hillside that used to be a [garbage] dump. It went through a process of collective [clean up] efforts and planting seedlings.” — Cris dos Prazeres

Matheus Botelho, a SFN youth organizer and resident of the Coreia favela in the municipality of Mesquita in the Baixada Fluminense, introduced the discussion on food sovereignty. He talked about ultra-processed foods and “the right of everyone to access healthy food in a regular and sustainable way, based on the cultural and food diversity of their own people and region.” He then introduced the third discussion question.

What are the Strategies and Initiatives to Fight Hunger in Your Territory?

Francisco Xavier Sobrinho, Ticote, shared his caiçara experience and how it has been affected by ultra-processed foods.

“I come from a background where our diet was very much based on what we produced. We fished, we harvested all the food from the fields. With this issue of industrialization, we lose the habit of eating well… but, within agroecology, encouraging people to plant and harvest their own food, without chemicals… we don’t need to buy these industrialized products for us to have a healthy population.” — Francisco Xavier Sobrinho, “Ticote”

The Black Mothers of the Amazon Collective is made up of Black women of different ages and strengths. Photo: Personal Archive

Maria Luiza Nunes highlighted that, especially for communities that base their food on their way of life, climate change brings a high degree of food vulnerability. She pointed to the danger of the Marco Temporal being approved and high rates of contamination of rivers and fish. Her hope is the resumption of good living and the Ubuntu way of life.

Still on the issue of health, Nunes said that medical services are precarious locally. However, in addition to traditional medicine, local communities also seek forest medicine. Climate change is a concern due to its environmental impacts and the risk it imposes on the conservation of traditional knowledge inherited from ancestors.

“We have the turu soup [made with the teredo mollusk], the garrafadas [medicinal herbs, roots or plants steeped in alcohol or water for long periods], the melador, you know? Those remedies, those medicines that were made with products of the land; and here we do have this blessing of the elders… backyards here are true living pharmacies!” — Maria Luiza Nunes

How to Engage Youth in the Climate and Environment Agenda?

When asked the final question on how to engage youth in the climate agenda, Ben Hur stated that critical, environmental education and art are tools to raise awareness among young people. These are efficient and effective strategies to mobilize young people in the fight for the environment.

“We ended up using theater and music to raise awareness about throwing garbage in the ditch… We were just harming ourselves… Plastic bottles, for example, are now a musical instrument for us, but for a long time they were one of the major causes of flooding in the Getúlio Vargas subdivision. So, we ended up using theater and music so that we could get through to these youth.” — Ben Hur Flores

Lia Esperança added to the debate by sharing local teachings carried out in Vila Nova Esperança: “We have our kitchen, which we call an experimental kitchen, because we cook Non-Conventional Food Plants (PANCs), which many people do not know, which are food and many people do not know.”

Some of the participants of the 1st National Sustainable Favela Network Exchange which took place online on June 6, 2023

3rd Session: Cultural Circle

Gisele Moura, environmental scientist and coordinator of the team that manages activities designed by and for the Sustainable Favela Network, led the last part of the exchange: a cultural circle based on affection and cultural exchanges. Here, the diversity of places, people, and experiences represented in the SFN exchange became even more evident. Moura introduced questions to kick off the exchange: “What brings your community together? How do we maintain our networks and purposes? How can we walk together? What is ideal, what is possible?”

Ben Hur paid “homage to a girl from Pelotas, from the Getúlio Vargas subdivision, a rapper named Daiane Alves, known as Preta G, a girl who went to Complexo do Alemão on our first trip in 2008. She passed away and today the street in front of our headquarters is named after her. The first rapper [with a street named after them] in an extremely conservative city.”

Tata Luandenkossi shared a tribute in song format, which he wrote when he visited the Tainã Culture Center in Campinas, São Paulo state, a place focused on cultural appreciation. According to him, what touched him most was a ritual with a Baobab seed.

“We got there and he gave us a Baobab seed, we put it in our mouths, we tasted the Baobab, and then we took this seed to our community to plant. And that’s what I did:

‘In the Tainã house of culture, there is an axé [life force in Afro-Brazilian traditions] that moves us all

In the Tainã house of culture, there is a strength that comes from the baobab tree

In the Tainã house of culture, there is a force that comes from the baobab treeÔba ôba ô baobá, Ôba ôba ô baobá, Ôba ôba ô baobá, Ôba ôba ô baobá’.” — Tata Luandenkossi