Favelas as Affordable Housing

Contrary to popular belief, we can be well impressed and inspired by a great deal of what we see when visiting favelas in Rio. Numerous community projects exist in which favela residents themselves face a wide range of challenges head-on, developing their own waste collection, sewerage, daycare centers, literacy, support for the elderly, art, literature, sports, mobility, community soup kitchens, nutrition, hygiene, dance classes, and much more. All of these projects also aim to raise awareness among the beneficiaries and to compensate for lack of public investment.

Contrary to popular belief, we can be well impressed and inspired by a great deal of what we see when visiting favelas in Rio. Numerous community projects exist in which favela residents themselves face a wide range of challenges head-on, developing their own waste collection, sewerage, daycare centers, literacy, support for the elderly, art, literature, sports, mobility, community soup kitchens, nutrition, hygiene, dance classes, and much more. All of these projects also aim to raise awareness among the beneficiaries and to compensate for lack of public investment.

There are many urban qualities in the city’s favelas, qualities that are difficult to develop through planning and which urban planners from all four corners of the world today endeavor to stimulate—often retroactively or facing significant cultural or political challenges. These include:

- Affordable housing in central areas.

- Density that promotes and enables quality public services without the excessive verticality that leads to isolation.

- Pedestrian-oriented planning encouraging better opportunities for community development and exchange.

- High use of bicycles and public transportation, which have a positive environmental impact on the local and global scales.

- Mixed use (residential over commercial lots) which reduces the need for transportation and stimulates community exchanges.

- Living near work, reducing expenses and time on transportation, as well as avoiding overloaded transit networks.

- Organic, or slow, architecture – iterative architecture that slowly evolves adapting to the needs and conditions of residents.

- High degree of collective action, which not only strengthens community bonds through mutual support, but offers economies (savings) with regard to a number of services and materials exchanged or offered in kind.

- Intricate solidarity networks.

- Advanced degree of cultural production.

- Entrepreneurship is encouraged and enabled by a constant exchange between residents, the possibility of creating businesses at home and the flexibility made possible by a historic lack of regulation.

In short, favelas are often natural examples of “New Urbanism,” aspired to by urban planners in the United States and elsewhere over the past 30 years with only mixed results given the challenges of planning to foster a sense of community.

Land Tenure in the Context of Gentrification

Land tenure has been a fundamental demand in the struggle for housing in Brazil and in many other countries. It is regarded as the most crucial step in attaining housing security, resisting forced evictions and demanding fair compensation.

Land tenure has been a fundamental demand in the struggle for housing in Brazil and in many other countries. It is regarded as the most crucial step in attaining housing security, resisting forced evictions and demanding fair compensation.

Today, land tenure gains attention in Rio de Janeiro, but this activity and debate come hand-in-hand with another new threat to housing rights. Despite the great uncertainty that favela residents face due to threats of eviction—with 8,000 already removed during the last couple of years in Rio, and 40,000 under risk of removal—our biggest challenge today is presenting itself in a new form, as gentrification.

With regards to forced evictions we’ve had plenty of accumulated experience and knowledge in Rio de Janeiro. It’s what we are most familiar with. And we have developed some ways of confronting them. Though difficult, there have been successful cases, and legal mechanisms to defend resident rights exist. Some favelas are able to join forces and mount successful resistance campaigns. For the people are already familiar with this “monster,” social movements have been able to establish certain laws, the international media sees it as cruel, and human rights institutions are constantly watching.

In the meantime gentrification, in favelas being called “white removal” or “market eviction,” runs the risk of displacing many more people from their homes, modifying their locations into elite areas, all without needing to legitimize itself. This because the market is seen as “natural” and gentrification as “inevitable.” At the same time, cariocas find themselves with less experience to deal with this phenomenon in Rio: it caught us by surprise.

What is it?

Gentrification is a common process in major cities of the world today, some of which have experienced it for four decades now.

Gentrification is a common process in major cities of the world today, some of which have experienced it for four decades now.

It happens when, for some reason—be it due to public or private investment and improvements, lack of land or real estate options elsewhere, an attraction for the exotic, or lack of accessible prices in other more attractive locations—a small group in search of housing starts moving into the area.

When gentrification happens spontaneously, this is often a group that enjoys and takes the place as it is, unaffected by any prejudices associated with it. In some cities these have been artists, in others the homosexual community. In others, students or young families.

In Rio’s case, this phenomenon has been associated with the arrival of foreigners: young foreigners come to study or work in Rio but often don’t carry the same prejudices that the local middle-class acquires from an early age.

In reality, though, we can distinguish at least three groups of “gentrifiers” in Rio: young professionals and foreigners, speculators, and favela residents able to pay higher rents. With the establishment of UPPs (Pacifying Police Units), rents have risen in all UPP communities, and this rise is generally not being paid by foreigners and speculators, but by favela residents who, despite the hardship, manage to pay higher rents.

Traditionally what happens with gentrification is that the arrival of the first group of “outsiders” triggers a process in the local market where prices start rising and the area increases in value. The first group is not in itself “the problem,” for they usually sympathize with the area and arrive without the intention of modifying it or speculating. But this group unintentionally notifies the property and commercial market of the area’s potential. That’s when the market enters the scene, sometimes slowly and partially, other times quickly and in a way that completely alters the area’s character. Ultimately an area is “gentrified” when a significant portion of the population has been displaced due to economic eviction.

Recipe for Gentrification

In Rio’s case, favela gentrification is making fast progress because of a particular “recipe for gentrification” currently underway in Rio:

In Rio’s case, favela gentrification is making fast progress because of a particular “recipe for gentrification” currently underway in Rio:

1 – Economic resurgence has increased the overall demand for housing in Rio de Janeiro, and the ability of some to pay more.

2 – Rio today is a hyper-valorized market with:

- Relatively few areas attractive to a large portion of the population (due to lack of services and opportunities in the vast majority of the metropolitan region)

- Without much possibility for expansion in these central areas

- Without a mass transit system to enable easy circulation and, with it, the decentralization of housing

- A central business district that concentrates a majority of jobs.

3 – In Rio de Janeiro land and real estate prices are unregulated. What has contained prices in central favelas historically was a combination of a stagnant economy in the region as a whole, the presence of the drug traffic, lack of regularization of land titles and missing public services.

4 – The arrival of a UPP in a favela causes an immediate rise in real estate prices inside and surrounding the community, pressuring renters.

5 – Often the first investments following the arrival of the UPP are those that compromise vulnerable residents’ ability to stay: they are those public services residents already had access to, but must now pay (at times unreal) market rates for: electricity, water, communication, etc. That is, it doesn’t improve residents’ quality of life, it only drags on their family income and makes it harder for them to afford to stay.

6 – Subsequently comes land tenure and, with it, property tax. As it is currently being handled, the process will force many homeowners to leave their homes unable to pay the additional expenses, as gentrification does elsewhere around the world.

Comparison and Regulation of Prices and Housing in Other Cities

At least around 25% of residents of any metropolitan area cannot by definition afford to pay market rates for housing. Many times, these are the people who build and maintain the city. They are also the most vulnerable, which any city has an interest in caring for so they don’t despair to the point of resorting to crime or becoming unstable.

At least around 25% of residents of any metropolitan area cannot by definition afford to pay market rates for housing. Many times, these are the people who build and maintain the city. They are also the most vulnerable, which any city has an interest in caring for so they don’t despair to the point of resorting to crime or becoming unstable.

It is for this reason that successful cities around the world recognize the importance of regulating the real estate sector to facilitate access to housing for their lower socio-economic residents. This is done in a variety of ways. In Hong Kong, 49% of people live in public housing. In London, 24% receive a rent subsidy. In New York, rent controls have existed since the 1940s; today, there are 600,000 public housing units in New York and new housing developments incorporating affordable housing are permitted to add extra floors. In Singapore, 90% of real estate belongs to the government. In Zurich, approximately 30% of residents live in cooperatives, created decades ago due to real estate speculation and the need to guarantee affordable housing. All are inclusion policies for those low- and middle-income residents of central areas that promote balanced, healthy and inclusive urban development, with people able to offer a range of services in the various urban areas, limiting the formation of ghettos.

Today, it is general consensus among city planners that cities must incorporate and guarantee access to affordable housing in central areas.

Currently in Rio we’re going against this consensus which is leading to an (even more) unsustainable situation. Public officials leading the current process say they are building a “global city,” but they are doing so without the policies that make such cities work. At the same time one could argue the world is no longer in need of “global cities,” but of singular cities. Global cities often lose something important–their origins and originality. Something new is now called for.

With that, let’s instead be optimistic and think creatively about how Rio might take advantage of its history and build something unique for its future. How we might learn from the accumulated knowledge of decades of experience in major cities in the developed world, without committing the same mistakes. In other words, how can we take advantage of this moment, with the knowledge we have today about Rio and other cities, plus the information and technologies which we have access to today, to build something better?

The Potential of Rio’s Favelas

Assuming we recognize the importance of guaranteeing accessible housing (in all senses), and recognizing the qualities of favelas mentioned earlier, how do we move forward?

Assuming we recognize the importance of guaranteeing accessible housing (in all senses), and recognizing the qualities of favelas mentioned earlier, how do we move forward?

How, in Rio, will we meet this need, recognized and fulfilled in diverse forms across the world’s large cities? And might we do an even better job at it, to serve as an example for 3 in 9 billion people the UN predicts will be living in ‘slums’ by 2050? This is the debate we need to have.

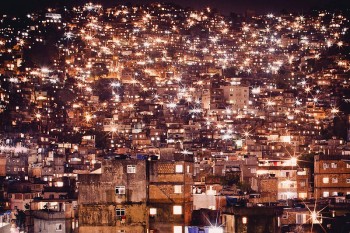

Let’s start with where we are now. How have we in Rio met the need for housing so far? Historically this has been accomplished through the favelas, today housing 24% of Rio’s population. This percentage is comparable with those cited above with regard to housing subsidies in other cities around the world.

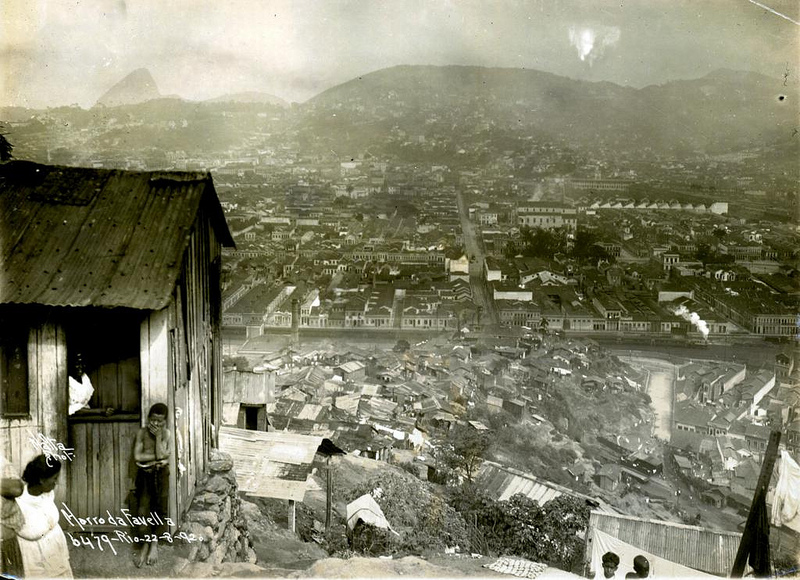

After a 115 year history of favelas, what we have today in Rio are 600 unique experiences, providing housing for 23% of the population. What is a favela? From an urban planning point of view, if we have to simplify and apply a single term to all favelas, we can say that a favelas are, simply:

- Neighborhoods that emerge from an unmet need for housing.

- Established and developed without external or government regulation.

- Their original blueprint established and developed organically and by residents themselves.

- Continuously evolving based on culture, access to resources and jobs.

Thus, today in Rio we have 600 districts in a process of organic development. Some experiences did not work, and its residents want nothing more than to be resettled in better conditions. But the large number of communities where residents are bitterly opposed to resettlement is proof of the value and qualities of these communities.

We cannot compare the favelas with any other type of residential neighborhood for the following reasons–favelas are built brick by brick, stone by stone, by their inhabitants and their ancestors. So much history embedded in these spaces cannot be ignored. For some this is irrelevant, for others it is absolutely vital. Favelas have a historical value to be defended and their inhabitants the right to not only opine, but to conduct their future development, should they wish to do so. In fact, they have already proven to be more than capable by building these neighborhoods into what they are today. All the qualities contained therein are a product of their residents and history.

We cannot compare the favelas with any other type of residential neighborhood for the following reasons–favelas are built brick by brick, stone by stone, by their inhabitants and their ancestors. So much history embedded in these spaces cannot be ignored. For some this is irrelevant, for others it is absolutely vital. Favelas have a historical value to be defended and their inhabitants the right to not only opine, but to conduct their future development, should they wish to do so. In fact, they have already proven to be more than capable by building these neighborhoods into what they are today. All the qualities contained therein are a product of their residents and history.

Returning to the issue of land tenure, we need to consider these favela qualities when we think about how to regulate land ownership. Is it worth titling just for titling’s sake? Why do we want tenure? If it is to increase security, does land tenure always guarantee increased security? If it is to increase the value of homes with the intent of strengthening social justice, will land tenure really increase social justice if we take into account all its impacts? The answer is not always simple.

What is important now, thinking about the future, is to recognize this history, the achievements, qualities and solutions derived from favelas, as a starting point for any discussion about the future urban development of Rio, and plans to improve access to housing. Everything should take this into consideration, from public housing projects, which need to be developed with these qualities incorporated; to favela upgrading programs, which should not compromise these qualities while meeting the challenges of each community; even land tenure must be handled in a way that maintains those qualities.

It is fundamental that decisions are made by favela residents with access to the best information possible.

Introducing the Community Land Trust

As a point of reflection, an interesting mechanism for this, already developed in several places including Africa and the Middle East, but growing faster in Britain and the United States, is called the Community Land Trust. This model of affordable housing, which has been spreading since the 1970s, has proved itself to be the most resistant to upswings and downswings in the economy, in periods of speculation and foreclosure.

How it works:

- A nonprofit entity is created, whose administration is run by residents and professionals voted on by residents, whose purpose is to manage—in perpetuity—the land on which residents reside.

- Although families are the proprietors and build their own homes or other structures, the land itself remains ‘under tutelage’ of the community as a whole, and thus protected from the vagaries of the housing market.

- CLTs are based on geographic location, defined by a certain geographic size of neighborhoods, or areas whose boundaries may change over time.

- Most CLTs, adhering to their mission to promote access to affordable housing, regulate prices and resell housing to recipients in accordance with this mission. This monitoring function is there to ensure that those who need it have access to housing, while ensuring a fair return to owners on their investments, although avoiding drastic swings in property values that trigger cycles of gentrification of neighborhoods.

- To get organized as a Community Land Trust provides numerous benefits to the community, facilitating and promoting their ability to organize and manage their own community development, according to a mission defined by the community itself. This may include, in addition to a goal of maintaining affordable housing, the development of quality upgrades, maintenance and strengthening of the local culture, and other factors to be defined by residents themselves.

Conclusion

We should insist on a customized urbanization of each favela community, where a genuine participatory process occurs, taking into account the strengths and challenges of the site; prioritizing, and separating the items that (1) can improve through resident action, (2) require public investment, and (3) the community can accomplish through partnerships. Then upgrades and services should come, fulfilling the needs prioritized by the community, followed by land titling that retains the qualities as determined during the whole process.

It is worth noting that all the elements necessary for this to happen exist today. Communities organizing, some for decades, around local demands. Studies and more studies on the impacts of various policies on the city and its favelas. The recent demonstrations in Rio show the tremendous public desire to establish a new way of thinking about the city. Information today is flowing in an ever more efficient way, thanks to social media. And we have decades of local and global knowledge regarding successful and unsuccessful policies well within our reach. With this, we cannot let this moment go to waste. It’s time to create our Recipe for Integration.

— by Theresa Williamson, Ph.D., urban planner and Catalytic Communities’ Executive Director

published May 16, 2013