Favela Community Land Trust Community Workshop: Methodology and Practice

In Rio de Janeiro, from August 23 to 27, 2018, Catalytic Communities (CatComm) organized a series of workshops on Community Land Trusts (CLTs), together with a special delegation from the Caño Martín Peña CLT based in San Juan, Puerto Rico. The workshops were designed to discuss this urban planning tool and consider its potential applicability in Brazilian favelas. Over the five days of workshops, 130 individuals participated, including fifty community leaders and residents of Rio’s favelas. The workshops were organized in partnership with the Rio de Janeiro State Public Defender’s Office, the Pastoral de Favelas, the Rio de Janeiro Architecture and Urbanism Council (CAU), the Laboratory for Studies of Transformations in Brazilian Urban Law (LEDUB), the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy (LILP), and the Global Land Alliance.

The first event reported on below, was the Community Workshop, which took place on August 23 at the Rio Public Defender’s Office Foundation School (FESUDEPERJ), specifically featuring residents and community leaders from favelas in Rio and community leaders from favelas in Puerto Rico. On August 24, at the same venue, the Legislative Workshop was held for technical advisors and members of civil society—lawyers, housing movements, favela organizations, architects, engineers, and urban planners—interested in discussing the legal possibilities for applying the CLT model in Brazil. On August 25 and 26, local community workshops were hosted in favelas in collaboration with residents—the first in Barrinha and the second in Vidigal. On August 27, a morning gathering was held to present the CLT model to Brazilian authorities, as well as representatives of public agencies and political parties. In the afternoon, the Puerto Rican delegation presented their final conclusions to the general public at the headquarters of the Rio de Janeiro Architecture and Urbanism Council (CAU).

On the first day of the workshop series on August 23, residents and leaders from Rio’s favelas met with a delegation from the favelas of the Caño Martín Peña, represented by four individuals: community leaders Mario Núñez and Evelyn Quiñones from the Group of Eight Communities (G8), which leads local organizing, and Lyvia Rodríguez and Alejandro Cotté from the ENLACE Project, a public program that was created to facilitate the establishment of the Community Land Trust (CLT) and support community upgrading over 25 years. The ENLACE Project is effectively a public local development agency working on behalf of residents of the eight Caño communities.

Over the course of the day, facilitators applied methodologies developed over years of community organizing that ultimately led to the establishment of the CLT in San Juan. According to this methodology, when discussing land tenure security, it is important to contrast specific models and methods of obtaining land tenure security only after discussing the local context. This discussion begins by (1) assessing the community’s qualities, (2) documenting perceived or actual threats facing the community, and finally (3) debating the precise reasons for which residents seek land titles.

To develop an effective instrument for guaranteeing tenure security, these three factors must be taken into consideration in order to (1) develop a solution that preserves (and even strengthens) the community’s existing qualities; (2) guarantees protection against threats that the community is currently experiencing or believes it will likely face in the future; and (3) ensures that the real (and not theoretical) motives for desiring land titles are those that are addressed with the acquisition of titles.

On the morning of August 23, the representatives from fourteen communities in Rio and one from Minas Gerais State that were present at the event discussed these qualities, hopes, and threats with regard to their communities and land tenure security. In total, there were 39 participants from Rocinha, Vidigal, Quilombo do Sacopã, Bancários, Indiana, Complexo da Maré, Rio das Pedras, Prazeres, Vila Operária (Nova Iguaçu), the Shangri-lá Cooperative, Complexo do Alemão, Rádio Sonda, Caetés, and Caminho dos Cabuis, in addition to the Eliana Silva Occupation in Belo Horizonte.

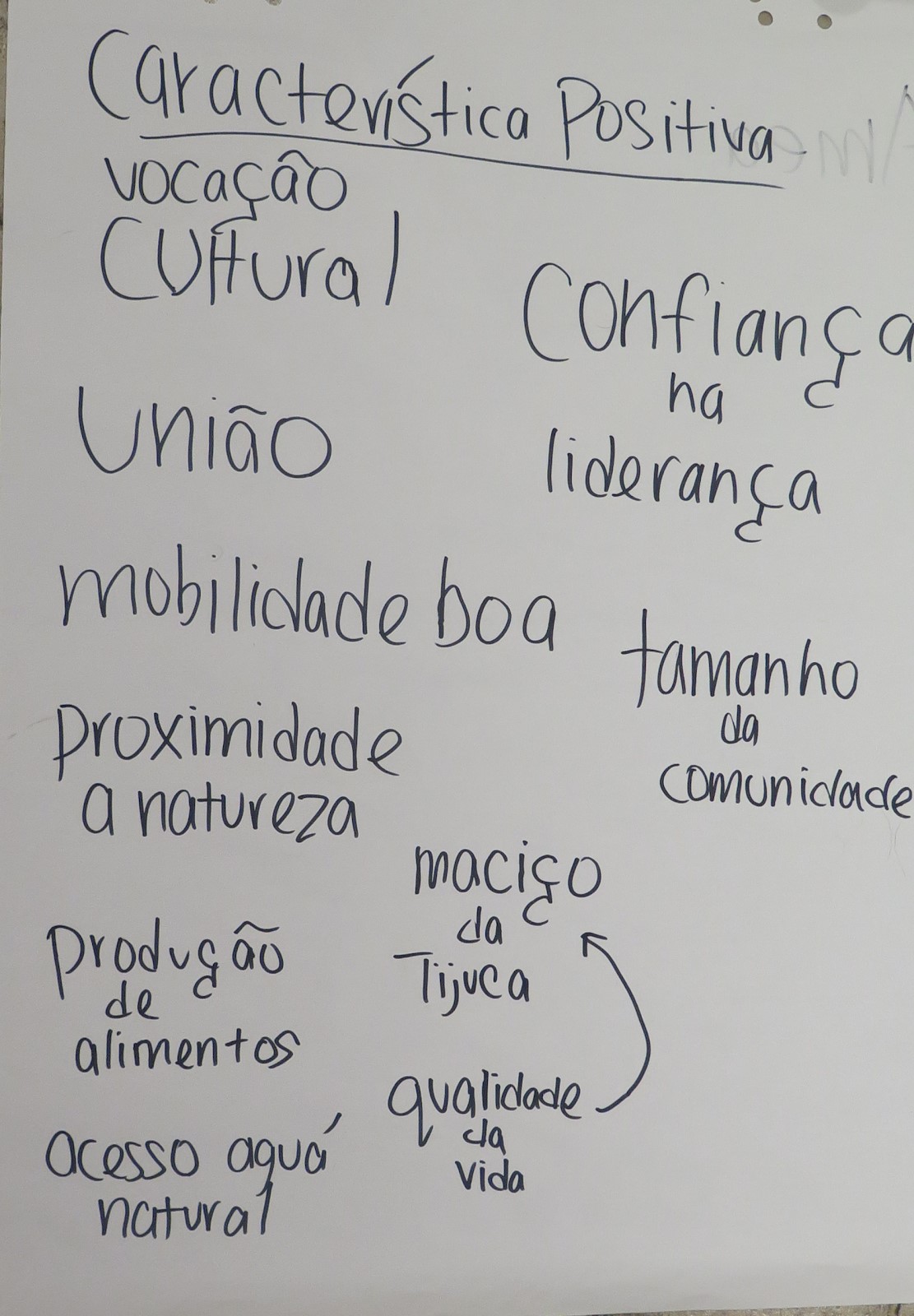

Participants split up into groups of ten so that each could describe the positive features of their respective communities and the main threats facing residents. Next, a representative from each group presented the results in a group activity involving all participants.

The activity highlighted a great variety of positive characteristics, showcasing the tremendous diversity of local realities in Rio’s favelas. These included: easy access to local commerce/strong local commerce; good mobility/proximity to public transit/easy-to-access location; diversity/cultural diversity; cultural vocation; proximity to nature, which promotes quality of life; unity; non-violence; community organizing and resident resistance; food production; access to natural springs; trust in local leadership; community size; dignity; coexistence; use of streets; familiar; and persistence/struggle, among others.

The activity highlighted a great variety of positive characteristics, showcasing the tremendous diversity of local realities in Rio’s favelas. These included: easy access to local commerce/strong local commerce; good mobility/proximity to public transit/easy-to-access location; diversity/cultural diversity; cultural vocation; proximity to nature, which promotes quality of life; unity; non-violence; community organizing and resident resistance; food production; access to natural springs; trust in local leadership; community size; dignity; coexistence; use of streets; familiar; and persistence/struggle, among others.

As far as threats, the same issues were repeated more frequently, often linked to market or government forces: processes of gentrification/the arrival of outsiders, real estate speculation, property repossession/expropriation, increased cost of living, actions by municipal/state/federal authorities, areas of environmental risk/landslide risk, drug trafficking/militias, lack of mobility, psychological terror inflicted upon residents, lack of building regulations, and lack of mechanisms to ensure residents’ permanence.

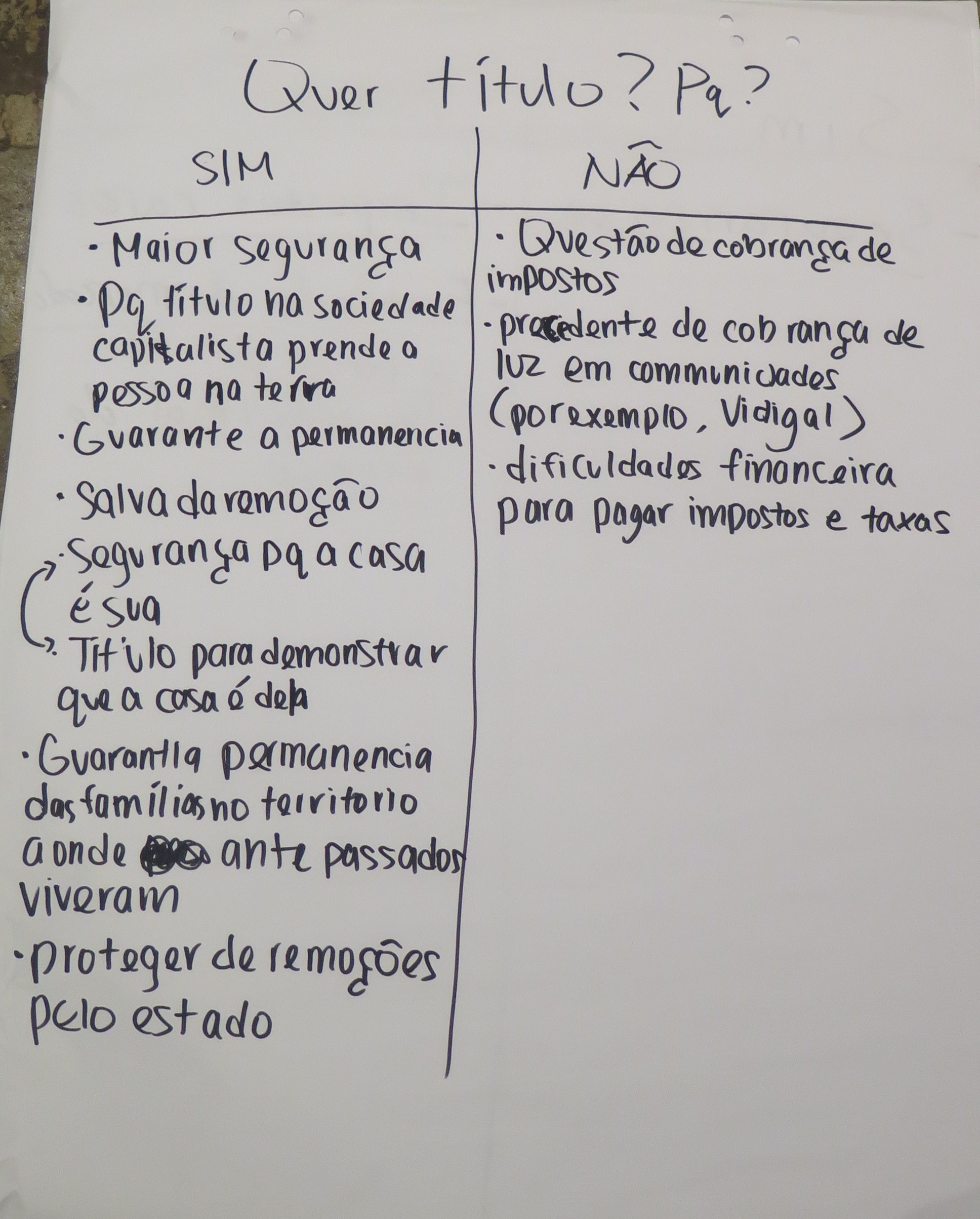

The second part of the morning activity sought to consider why residents seek land tenure security. To this end, in groups, participants discussed the reasons for which residents of their respective communities would or would not like land titles and regularization. Consultations conducted prior to the workshops identified examples of residents and local organizations that resist land titling—a fact that is rarely taken into account given the frequent assumption that land regularization and land tenure security are synonymous. Indeed, as we discovered with the experience of the Caño Martín Peña in Puerto Rico, sometimes regularization increases land tenure insecurity. For this reason, the communities of the Caño found the CLT to be a safer model of regularization.

The results from the second part of this activity demonstrated this inherent conflict. Residents would like to receive land titles and carry out land regularization since they believe it to be a tool to guarantee permanence and expand rights. Those who do not want land titles and land regularization warned that these processes increase the cost of living or encourage speculation and consequently reduce residents’ capacity to remain in their respective communities.

Subsequently, presentations were delivered by Tarcyla Fidalgo, lawyer and urban planner from the Laboratory for Studies of Transformations in Brazilian Urban Law (LEDUB) at the Institute of Urban and Regional Research and Planning (IPPUR) of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ); Theresa Williamson, urban planner and executive director of Catalytic Communities; and Lyvia Rodríguez, urban planner from the Caño Martín Peña CLT.

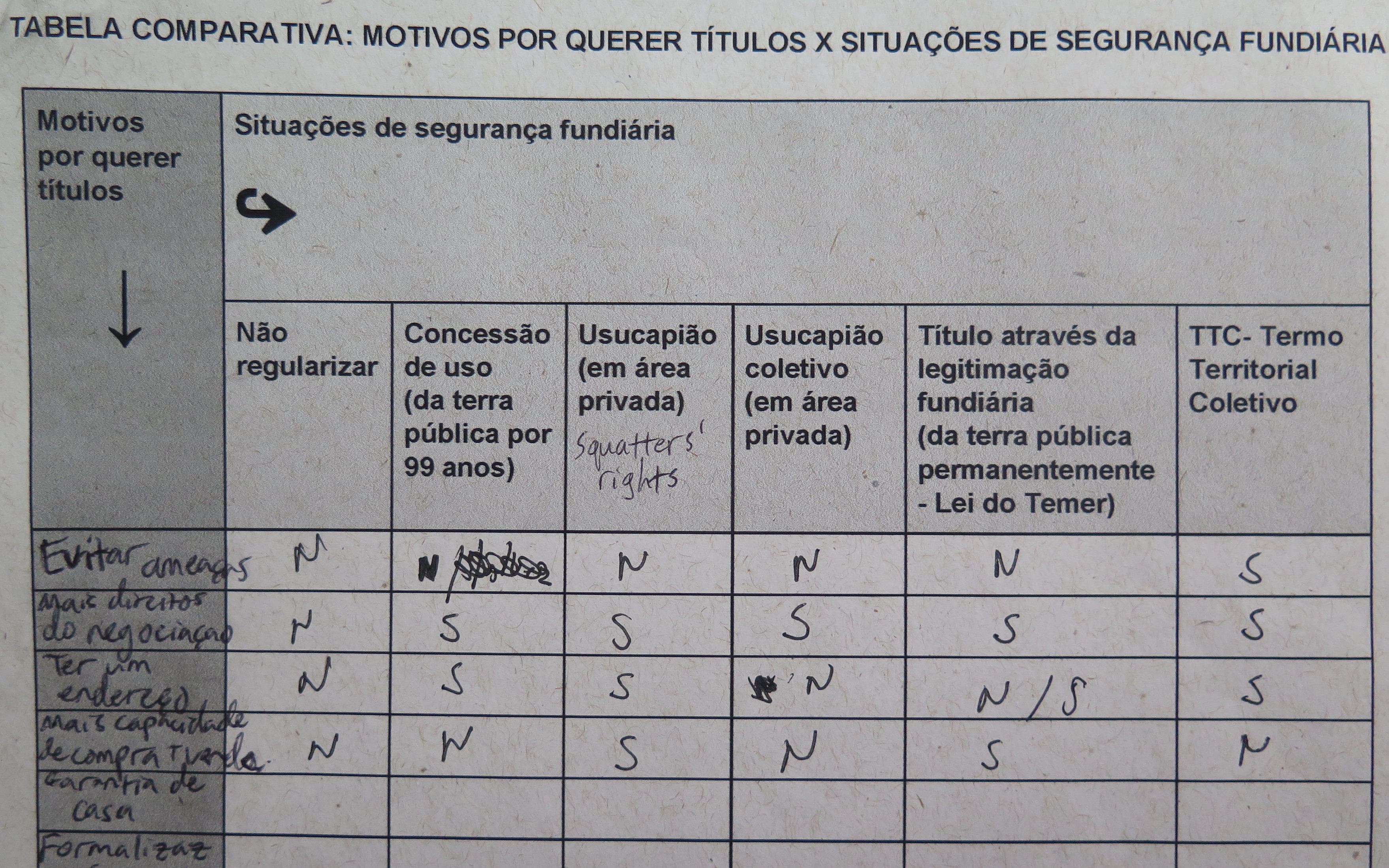

Fidalgo presented the main strategies and tools for land regularization available today in Brazil in order to contextualize the current limitations and scope of these tools and to create a dialogue with the results presented in the previous group dynamics. The tool presented for land rights on public land is the special concession of use for housing purposes; and on private land is adverse possession (either individual or collective). Fidalgo also presented a new tool to enable full titling on public land known as land tenure legitimation, as established by President Michel Temer’s recent land regularization law.

Shortly after, Williamson briefly presented the Community Land Trust (CLT) model, speaking about the emergence of CLTs in the context of the civil rights movement in the United States in the 1960s and the expansion and variety of the model’s applications since then. As she explained, research in the U.S. has shown that the CLT is the most robust model for promoting affordable housing—capable of surviving both economic highs and lows when such pressures would normally reduce the chances of low-income citizens being able to remain in their homes. Next, Williamson discussed the context of evictions and gentrification in Rio’s favelas over the past ten years, associated with the process of real estate speculation in these areas. Williamson connected these issues to the need for a tool that brings together security of permanence, the strengthening of community organizing, and local development. Williamson then presented the basic principles of CLTs, relating them to the real needs of Rio’s favelas in order to conceive of a CLT model that applies to the Brazilian reality.

The universal aspects of the Community Land Trust model are:

- Voluntary participation: No one is obligated to participate in a CLT. Individuals may freely choose to join an existing CLT, to vote with their neighbors in developing a new CLT, or to pool individual titles to property. Opting in is a must.

- Collectively-owned land via the CLT: The CLT institution is the owner of all land on which a CLT operates, and is managed collectively.

- Individually-owned homes: On the CLT’s land, the buildings within the CLT are owned or rented by residents with owners able to buy and sell their properties. This may involve selling at pre-established prices and/or purchasing and reselling homes via the CLT itself.

- Community control of the CLT: The CLT’s management is voted in by residents of the community and determines what community qualities will be developed by way of the CLT (e.g. housing, commercial activities, gardens, culture), withpermanent affordability as the core quality common to all CLTs. Community residents vote for a tripartite board to the CLT which includes owner-residents, neighbors with a direct interest in the community, and technical advisors from outside the community.

- Permanently affordable: The CLT’s primary mandate is to maintain and develop the CLT to keep it affordable for perpetuity.

To demonstrate the real application of this model in favelas, Lyvia Rodríguez, an urban planner currently acting as Executive Director of the Caño Martín Peña CLT, presented on the Community Land Trust implemented in the favelas of the Caño Martín Peña. The presentation began by contextualizing the issue of socio-spatial inequality in Puerto Rico and the historical attempts to evict the Caño’s favelas, most recently due to their location in areas that are highly valued by the real estate sector—reflecting countless similarities with the Brazilian context, specifically in Rio de Janeiro. In addition, Rodríguez played for the Rio audience a short video utilized in educational campaigns in Puerto Rico (below), and discussed the process of constructing the CLT in Puerto Rico, explaining its basic operating mechanisms and benefits for residents. Of great interest were the countless initiatives beyond land regularization that were made possible by the creation of the CLT, as well as the unity generated throughout the process. In the case of the Caño, the CLT organizes thirty initiatives that strive to develop critical thinking and to encourage democratic participation among residents. Over 1,500 youth are actively involved in these projects, which include violence prevention initiatives, community businesses, and a school for leadership and social transformation, among others. These projects train young leaders, who are then included in CLT decision-making.

Following these presentations, participants were asked to complete a table identifying the benefits and limitations of each land titling and regularization instrument—those that already exist in Brazil (presented by Fidalgo) and the CLT model (presented by Rodríguez)—in relation to the threats discussed during the first group activity of the morning.

Following these presentations, participants were asked to complete a table identifying the benefits and limitations of each land titling and regularization instrument—those that already exist in Brazil (presented by Fidalgo) and the CLT model (presented by Rodríguez)—in relation to the threats discussed during the first group activity of the morning.

The afternoon was reserved for a community exchange between workshop participants and the delegation from the Puerto Rican CLT, represented by community leaders Núñez and Quiñones with the support of Rodríguez and Cotté. After presenting a video that introduced the CLT, the Puerto Rican visitors further discussed their experiences, describing the process of organizing residents in their struggle for permanency, together with the technical advisors. They then opened the floor for questions so residents and community leaders from Rio favelas could clarify any uncertainties.

The knowledge exchange exceeded the organizers’ expectations, with all participants demonstrating a great deal of interest in learning more about the CLT. Generally speaking, several questions arose concerning the structure and organization of the CLT in Puerto Rico, as well as questions about how this model could be applied and adapted to Rio’s favelas. Lastly, the workshops scheduled to take place over the following days were announced in order to deepen this knowledge-sharing process and to clarify additional questions.

For more information about the CLT model or to join the CLT Working Group, please contact us at ttc@comcat.org with the subject “GT do TTC – Interesse em participar.” Meetings are conducted in Portuguese.