The Tiny NGO That Changed Reporting on Rio’s Favelas – CatComm Featured in The Development Set

The article below about Catalytic Communities’ work with journalists in the years leading up to and during the Olympics was published on August 24, 2016, in The Development Set. For the full article click here.

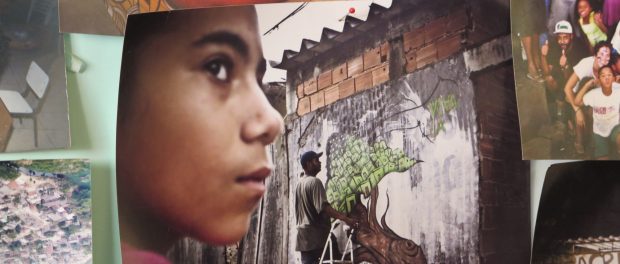

“Rat kids” digging through garbage. Millions of people squatting “in huts amid sewage and sorrow.” “A world of youth gangs, violent crime and drug dealing” that represents a “no-go zone.” These were among the descriptions of Rio’s favelas that appeared in major global media outlets as the city geared up to host the Olympic Games.

These images were exactly what Theresa Williamson had feared. After 16 years working with residents of favelas, the informal settlements that house nearly a quarter of the city’s population, she knew that reporters parachuting in to cover the Games were likely to fall back on harmful clichés. As in many cities, media reports on Rio’s informal settlements have often depicted them as decrepit, dangerous, and miserable. They’re the same stereotypes that U.S. swimmer Ryan Lochte and his teammates drew on to concoct their bogus story about being robbed at gunpoint just over a week ago.

Many of the 1,000-some favelas do face problems with poor sanitation, inadequate housing, and violence. But the neighborhoods vary widely, and many are vibrant communities with productive economies and homes of concrete and brick. Drug violence garners sensational coverage, but only 37% of favelas are controlled by drug gangs, and less than 1% of residents are involved in trafficking. More nuanced coverage has emerged in recent years, but Williamson worried that the Olympics, which were expected to attract 30,000 journalists to Rio, would create a perfect storm: swarming reporters with tight deadlines, limited resources, and ignorance of the local language and landscape.

“We thought we might see an increase in poor, stigmatizing, and inaccurate reporting,” she said in a phone interview. “If journalists don’t have access to communities or story ideas, they ignore favelas or start producing the same old stereotypes.”

Through her tiny Rio-based nonprofit, Catalytic Communities (known as CatComm), Williamson and her colleagues decided to do what they could to change the narrative. Williamson, who was born in Brazil and raised in the U.S., founded the organization in 2000 as she completed research for a Ph.D. in city planning at the University of Pennsylvania. The group first launched an online database and a physical community center to support local initiatives in favelas. In 2008, it shifted to training communities in online publishing and social media tools. After Rio won its bid to host the Olympics in late 2009, the team — with the equivalent of just four full-time staffers and dozens of volunteers — focused on preparing for the deluge of coverage.

Drawing on the group’s network of 1,200 community leaders from around 200 favelas, they launched RioOnWatch, a hyper-local news site, in May 2010. They compiled online resources, including a list of more than 50 community leaders willing to talk to reporters. They sent newsletters suggesting under-covered topics that residents wanted to spotlight: a centuries-old favela facing removal, a neighborhood at risk of landslides and ignored by authorities, an Olympics media village built on a slave burial ground. After the Games started, they took nearly 30 journalists on “reality tours” that introduced them to favelas bearing the brunt of Olympics construction and community leaders fighting for sanitation and safe housing.

“Favelas were going to be part of the story,” said Williamson. “We saw an opportunity to create a more accurate, nuanced narrative that reflects their attributes and will allow us to help favelas develop in a way that’s community-driven after the Olympics. No matter how well a policy is designed, if communities are seen through stigmatizing lenses, the policies are poorly implemented.”

Williamson wanted reporters to avoid blanket descriptions of generic favelas and treat them as unique and specific places. She hoped to steer them away from dramatized descriptions of drug trafficking and shanties, which didn’t apply to the vast majority of favela residents. She wanted to make sure the media didn’t ignore the havoc that Olympics projects had wreaked on poor communities. Critically, she wanted reporters to understand that favelas were rooted in a history of slavery, state neglect, and stigma. And she aimed to highlight their often-ignored assets, such as self-organization and solidarity.

Mich Cardin, a New York-based freelance writer, found CatComm online and reached out a few days before landing in Rio in May. She had just gotten an assignment from Broadly, VICE’s women-focused site, for an article and photo series on favelas affected by Olympics construction projects. She didn’t know anyone in Rio, didn’t speak Portuguese, and only had two weeks.

Cardin read articles on RioOnWatch, and after she landed, David Robertson, a CatComm intern fluent in Portuguese, met her at her hotel. He took her to Vila União Curicica, where hundreds of residents had been evicted for an Olympics-related transportation project, and more were under threat. She met with residents such as Gloria, who’d lived there for 25 years and showed her the bulldozed lots her neighbors once occupied.

“I knew the media had sensationalized favelas, but I didn’t know to what extent,” Cardin said. “These were people who put whatever money they had into making their homes more comfortable, and there was a major sense of community. It broke a lot of stereotypes for me.”

Later, Cardin took an Uber by herself to a hilltop favela called Vidigal. The driver warily agreed to translate for extra pay, but no one would speak to her.

“My hunch was they were sick of receiving the same negative reputation in the media,” Cardin said. “It would’ve been nearly impossible to do this on my own.”

Will Carless, a correspondent for Public Radio International, has drawn on CatComm’s resources since landing in Rio a year ago. Recently, reading RioOnWatch inspired him to keep reporting on evictions, and the group connected him with a source in Largo de Tanque, a community that hadn’t received much coverage.

When Carless reported in June on Rio’s City of God, made famous in the eponymous 2003 film, CatComm’s spreadsheet of contacts linked him to sources there. He flipped the narrative by reporting on how the favela’s residents, who felt safe at home, found U.S. mass shootings scary. Though he was fluent in Portuguese, Carless said he couldn’t have reported in the City of God without a guide.

In August, CatComm took dozens of journalists to the City of God, along with a handful of other favelas and public housing complexes, to talk with residents about the impact of the Olympics and other challenges. Susan Ormiston, a veteran correspondent for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, attended parts of both tours. She had to produce five stories a week for television, radio and the Web during her month in Rio. Having reported in 25 countries, she was used to finding sources on the fly, but CatComm’s tours allowed her to quickly focus coverage on favelas neglected by Olympics investments. During a visit to a neighborhood called Rocinha, she captured its “sewage waterfalls” and talked to community leaders about their lawsuit against the government demanding sanitation services.

“I work in television primarily, and unless people see it, they don’t understand it,” Ormiston said. “[CatComm] almost acts as a translator, and I don’t mean language but cultures. It would be helpful in other countries.”

With a crowdfunded annual budget of $100,000, CatComm’s footprint is necessarily limited. In the international media, stereotypes have continued to seep through.

“We are driving up against one of the strongest social stigmas in the world today,” Williamson said. “There is also the judgment that comes from outsiders who assume that money equals happiness, or money equals development.”

But judging from the more than 200 articles that CatComm has actively informed, the organization has been successful at getting favela perspectives and voices in the media. That doesn’t include reporters who read RioOnWatch but didn’t contact the organization. Coverage has even increased compensation packages for displaced favela residents and stopped demolitions in some areas, Williamson said.

When the Games end, Williamson plans to release a multimedia manual to help other cities reproduce CatComm’s media strategy. The group will also publish an analysis of six years of coverage on favelas. RioOnWatch, meanwhile, will shift to supporting the nonprofit’s original focus: covering community-led solutions in favelas.

CatComm certainly has a point of view, but Williamson resists the idea that that the group is painting an overly rosy picture of informal settlements. “We never deny favelas’ limitations and problems, but that’s true for all communities,” she said. “Talking about the good doesn’t mean you’re romanticizing. The reality is the opposite: by not recognizing these communities’ assets, we are depriving them and ourselves of true development.”

Carless said journalists who draw on CatComm’s resources are not in danger of being biased if they follow professional standards. “I understand, as I think most correspondents here do, that CatComm has a certain worldview and agenda… Should journalists be spoon-fed everything that [Williamson] says? Certainly not! Should they seek out other alternate viewpoints? Absolutely! But that’s pretty basic journalism.”

For Williamson, getting the message out is critical: “Policies in Rio are counterproductive because they’re based on stigma. We need to come to see favelas for their assets, which will make it so much easier to deal with their challenges.”