Washington Post Cover Story: Stolen Lives and Childhoods of Favela Youth

On September 24, 2019, Catalytic Communities’ Executive Director Theresa Williamson was quoted in a Washington Post cover story which CatComm also supported with context and contacts.

The article, by Terrence McCoy and Marina Lopes, summarized the latest numbers on police killings of favela youth, stating:

“Between 2011 and 2017, the most recent year for which demographic data on police killings is available, the number of children and adolescents killed in a police shootout in Rio de Janeiro state more than tripled, from 55 to 193. In 2017, research shows, one of four teenage homicides were committed during a police operation…

The number of police shootings within 300 meters of schools and child care facilities in metropolitan Rio increased more than 50 percent in the first five months of this year, according to the Rio-based think tank Cross Fire. In the favela of Mare, 10 school days have been canceled this year on account of police operations, equaling the number from all of last year, according to the local group Networks of Mare.”

The thorough piece details the permanent emotional scars and heavy psychological toll such killings place on families and communities:

“(Kauã’s) father started to tick through what to do if the police came. Always be aware. Stop whatever you’re doing. Even if you’re scared, do not run.

‘They’ll think you’re a drug dealer,’ he said. ‘Everything to them is a drug dealer. They don’t see that there are workers here. There are families.’

Kauã promised he would do better. Rozario put him to bed on the mattress they shared, and in the morning, headed out for a day of fetching taxis for the wealthy people in the city.

It wasn’t until late when he returned. He found a community seething…

Barros and Rozario now sat in Rozario’s living room, beneath a giant picture of Kauã, discussing whether they could forgive — both the police, and themselves.

It’s a question Rozario can’t shake. When he comes home and sees his son’s bike, when he looks at his kites hanging on a nearby wall: What sort of father can’t protect his son? What kind of man lets a violent death go unpunished?”

In comparing older times and how “now there are fewer children out on the streets,”

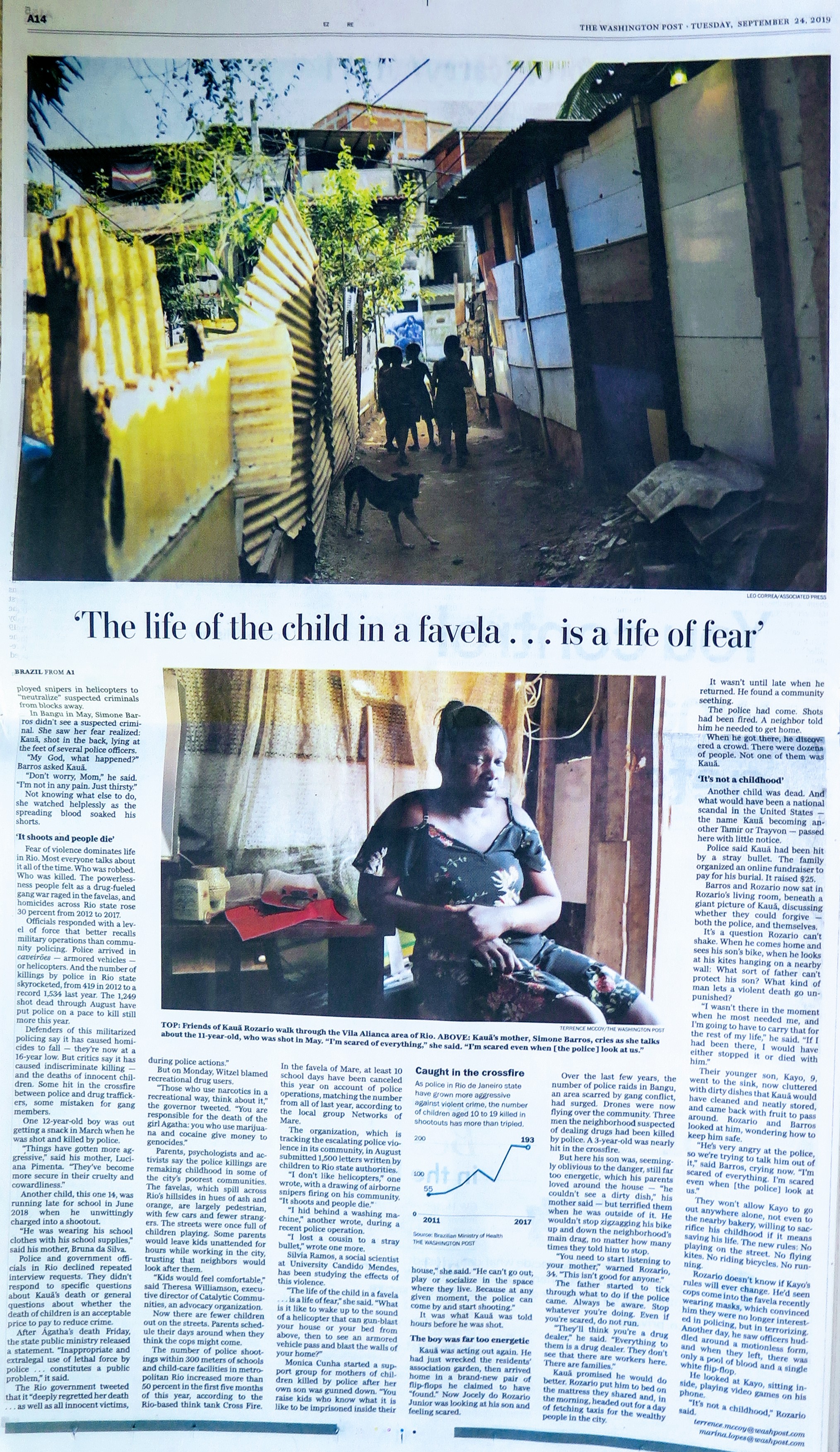

“Kids would feel comfortable (back then),” said Theresa Williamson, executive director of Catalytic Communities, an advocacy organization.

Whereas once:

“The favelas, which spill across Rio’s hillsides in hues of ash and orange, are largely pedestrian, with few cars and fewer strangers. The streets were once full of children playing.”

Today, with their younger son, Barros and Rozario:

“Won’t allow Kayo to go out anywhere alone, not even to the nearby bakery, willing to sacrifice his childhood if it means saving his life. The new rules: No playing on the street. No flying kites. No riding bicycles. No running.”