EccoVida Transforms Livelihoods through Recyclables at 3rd Sustainable Favela Exchange

The Sustainable Favela Network (SFN) is a project of Catalytic Communities (CatComm) designed to build solidarity networks, bring visibility, and develop joint actions to support the expansion of community-based initiatives that strengthen environmental sustainability and social resilience in favelas across the Rio de Janeiro Metropolitan Region. The project began with the 2012 film Favela as a Sustainable Model, followed in 2017 by the mapping of 111 sustainability initiatives and the publication of a final report analyzing the results.

In 2018, the project organized on-site exchanges among eight of the oldest and most established organizations that were mapped in the Sustainable Favela Network (one of which is the subject of this article), followed by a full-day exchange with the entire network that took place on November 10. The eight participants in the on-site exchanges featured in this series include six community-based organizations: the Vale Encantado Cooperative in Alto da Boa Vista, EccoVida in Honório Gurgel, Verdejar in Engenho da Rainha and Complexo do Alemão, Quilombo do Camorim in Jacarepaguá, ReciclAção in Morro dos Prazeres, and Alfazendo’s Eco Network in City of God. In addition, the exchanges visited two broader initiatives focusing beyond favelas with extensive experience in sustainability: Onda Verde in Nova Iguaçu and the Sepetiba Ecomuseum. The program is supported by the Heinrich Böll Foundation Brazil.

Watch the video that accompanies the exchanges featured in this series by clicking here.

The Afternoon of the Third Exchange: EccoVida, Honório Gurgel

“Who here throws money away?” Edson Freitas, founder of the NGO EccoVida, asked the group of Sustainable Favela Network (SFN) members gathered at the organization’s headquarters in the neighborhood of Honório Gurgel, in Rio de Janeiro’s North Zone, on Saturday, October 13.

Members of the group chuckled nervously, waiting to see if anyone would raise their hand. In a city that recycles less than 2% of its waste, for Freitas, everyone is responsible for throwing out money at their doorsteps: “What people think is trash is money to me.”

The North Zone’s history of government neglect and environmental degradation has made community-based organizations promoting sustainability in this region even more integral. Participants in the exchange witnessed one side of this story in the morning, walking the trails of the Serra da Misericórdia and learning about agroforestry with Verdejar in Engenho da Rainha. During the second half of the third day-long exchange, the SFN group discovered another key component of the region’s sustainability movement: EccoVida’s recycling facility, where the organization runs the Sustainable Brazil ECCO Point project. In the words of Freitas: “[Trash] collection is here, the benefits are here, recycling is here—and transformation is here.”

From Local to Global, and Back Again

Freitas founded EccoVida in 1999 as a means of collecting recyclable materials in his community of Morro Jorge Turco and surrounding North Zone neighborhoods. Driving the streets with a speaker system attached to his car, he repurposed the lyrics from a popular funk song to encourage residents to recycle household materials. Listen here:

“All residents can collaborate, separating trash to recycle. So I’ll teach you how to recycle, separating in each bag, what I tell you. There’s plastic, glass and metal, paper and cardboard. The AutoPET will pass, and collect it at your door. With this attitude, we’ll all help to reduce waste and stop flooding. Recycle this idea, my friend and my brother, hear this message that comes from the heart, help preserve the environment. Together we will live a happier future. Collect, collect, collect to preserve.”

EccoVida works to mobilize communities around “the idea that trash does not exist,” focusing on organizing cooperatives of recyclable materials collectors and centers to organize recycled materials, in addition to providing environmental education for schools and businesses, providing environmental consulting services, participating in Rio’s Zero Waste initiative, and organizing nature walks. EccoVida was even the city of Rio’s official recycling partner during the 2016 Olympic Games: 32 cooperatives and 220 trash collectors in EccoVida’s network returned from about one month of work during the Olympics with between R$4,000–7,000 (US$1,000–1,750) each—generating both financial and environmental benefits that represent EccoVida’s larger model.

Freitas explained that when he created EccoVida, his understanding of sustainability centered around his needs and his own experiences. With time, however, Freitas learned that environmental issues extend beyond his home, his street, and even his country. He now believes that protecting the environment is a global issue.

Freitas told SFN members that he fell in love with the work in part because of its potential to provide livelihoods, pointing to his own family as an example. He was able to support his three children through college because of his work with EccoVida: all three of them concentrated on some type of environmental studies. Now, EccoVida permanently employs 32 people, maintains recycling collection centers in communities across the city—including a partnership with SFN member initiative ReciclAção in Morro das Prazeres, in Central Rio.

Translating Awareness into Action

Despite recycling’s potential to transform livelihoods and the natural environment, Freitas blames its lack of popularity on corruption and poor public policies—and on a lack of public pressure to change these policies. “Today, there’s a huge omission on the part of society, principally organized civil society. There’s a lot of talk about sustainability but nothing is done in practice,” Freitas told the SFN group.

As Freitas “began creating ways of thinking” about the environment, he found that education wasn’t what was lacking: “I saw that what was lacking were options.”

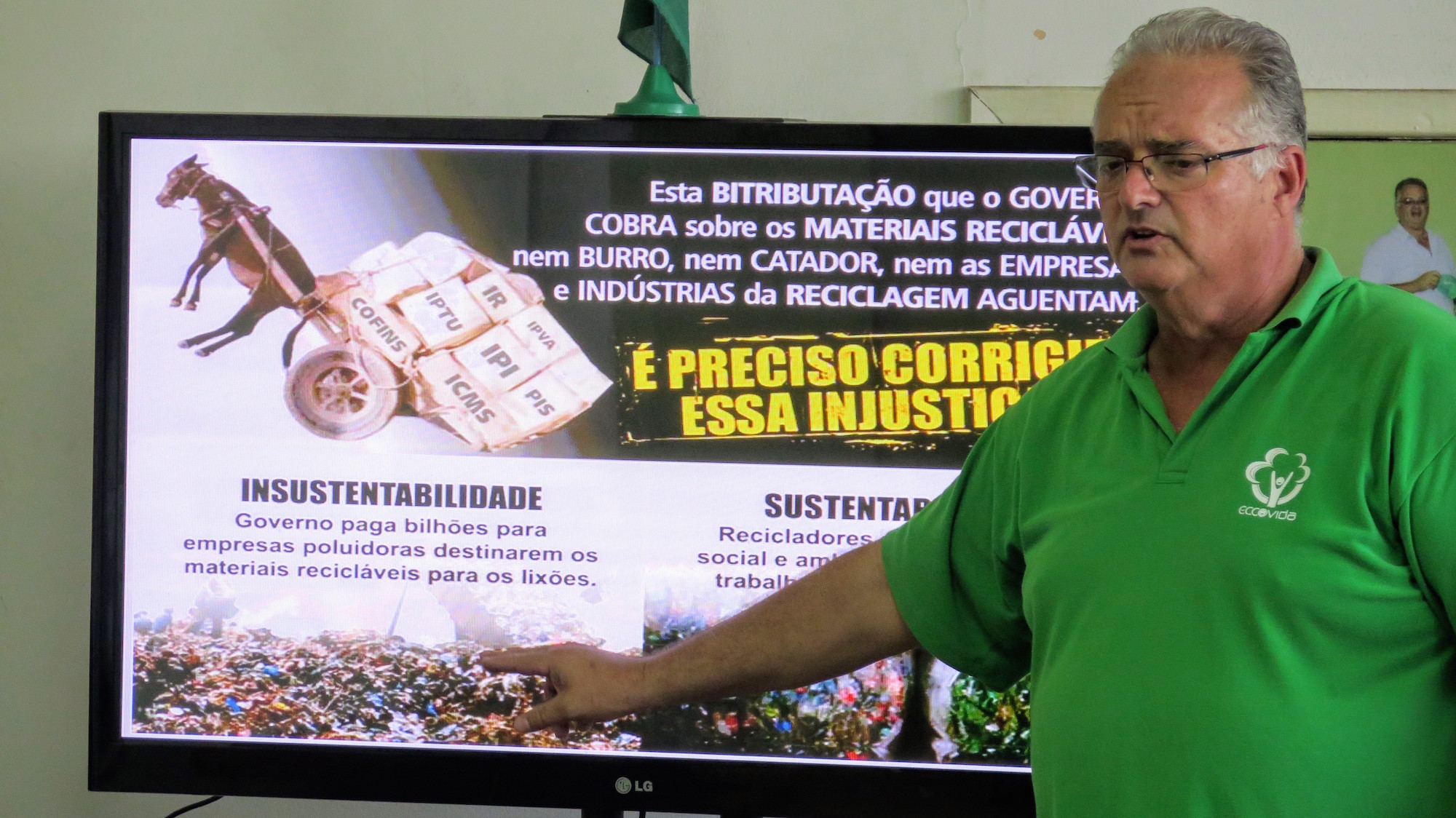

He explained that local government and tax systems incentivize environmental degradation more than they encourage protection, saying: “They consider me worse than the guy that cuts down trees.” Despite years spent lobbying for policies to promote recycling, Freitas has long seen his cause neglected by public authorities. “Who is interested in not preserving the environment, in not generating income? Who is interested in this not happening?” Freitas asked, pointing to special interests that maintain Rio’s landfills. “They know that we exist but they close their eyes… They don’t want us to grow, to become more formalized, because once people are more aware [of the benefits of recycling], they will change economic markets,” he said. Citing examples of unfair tax rates levied on recycling cooperatives, Freitas explained: “This is why I say that society has to participate. This is why I talk about a participatory mandate.”

EccoVida’s challenges do not stop at ineffective public policies. New technologies have made the collection and triage of recyclable materials increasingly efficient, a double-edged sword that has led to a reduction in EccoVida’s jobs, especially when it comes to their most profitable product: plastic bottles. “What I used to do in a month, [the machines] can do in less than a week,” Freitas explained, a development causing him to lament that “the capitalist market is cruel.”

Touring the Facilities, Exchanging Ideas

After learning about EccoVida’s creation and mission, participants in the SFN exchange toured the organization’s headquarters, visiting the entry point for recyclable materials and the open spaces where everything from plastic bottles to cardboard is separated into bags, each of which, when full of materials, can be exchanged for up to R$1500 (US$375). “When the package arrives at the consumer, they have a decision to make,” Freitas said. “Am I going to throw it in the trash, or am I going to continue the lifecycle of this package, preserving the environment? But this attitude of wasting this money and these raw materials doesn’t generate jobs and income. What is generated? Waste and pollution.”

As the group witnessed the transformation that occurs at EccoVida’s center, members shared recycling-related stories and questions. For example, Onda Verde founder Helio Vanderlei told SFN members that in Volta Redonda, a municipality located approximately 80 miles away, the local government pays recyclable materials collectors R$625 (US$150) per ton of recycled materials. Freitas expressed disbelief as the payment rate far exceeds that offered by the city of Rio. In Volta Redonda, however, cooperatives of recyclable materials collectors face a different set of challenges: they aren’t able to collect as many tons of materials as they potentially could due to a lack of training and resources needed in order to effectively mobilize, Vanderlei explained.

As the group witnessed the transformation that occurs at EccoVida’s center, members shared recycling-related stories and questions. For example, Onda Verde founder Helio Vanderlei told SFN members that in Volta Redonda, a municipality located approximately 80 miles away, the local government pays recyclable materials collectors R$625 (US$150) per ton of recycled materials. Freitas expressed disbelief as the payment rate far exceeds that offered by the city of Rio. In Volta Redonda, however, cooperatives of recyclable materials collectors face a different set of challenges: they aren’t able to collect as many tons of materials as they potentially could due to a lack of training and resources needed in order to effectively mobilize, Vanderlei explained.

Observing the pure quantity of recyclable materials in EccoVida’s headquarters alone, several SFN members grew excited by the potential of bringing sustainable jobs to their communities. Representatives from the Sepetiba Ecomuseum, for example, asked Freitas how they could go about starting recycling collectives, brainstorming how they could collect and transport materials and who from their network would be interested in participating. As the third Sustainable Favela Network exchange concluded, these moments ensured that EccoVida’s materials would be far from the only things repurposed from the day.

View our photos from the visit to EccoVida (or click here):

Read up on all of the 2018 Sustainable Favela Network exchanges here.