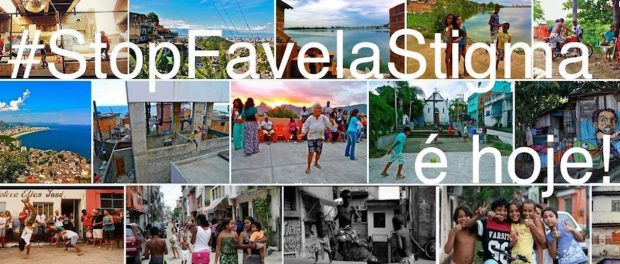

CatComm’s Social Media Campaign #StopFavelaStigma Highlights Resistance and Creativity in Favelas

Also using #MyFavelaIs and #MyFavelaIsNot, campaign engaged 85,000

As the Olympics were about to start, on August 3, 2016, Catalytic Communities ran a one-day social media campaign via the RioOnWatch Facebook page with the intention of denouncing the unfounded stigma associated with Rio’s favelas. Using the hashtag #StopFavelaStigma, over the course of the day we published articles and shared posts highlighting community voices to counter the damaging stereotypes that reinforce prejudice against residents of favelas.

The hashtag gained significant traction on social media: a simple Facebook search reveals over 85,000 “People Talking About This”—a metric which includes likes, comments, shares, and tags on posts containing the hashtag.

Representations of favelas

Kicking off the #StopFavelaStigma campaign with an article entitled “Favelas, Popular Territory,” community journalist Daiene Mendes from Complexo do Alemão wrote:

“The favelas should not be thought about as something exotic, distanced from reality or pitiable. Favela residents carry with them the strength and energy to transform realities. I like to say that almost every favela resident is an activist, because resistance precedes activism, and the only thing that defines the favela context is struggle and resistance.”

Daiene’s words speak to favela residents utilizing their skills and projecting their voices to make positive changes within and beyond their communities.

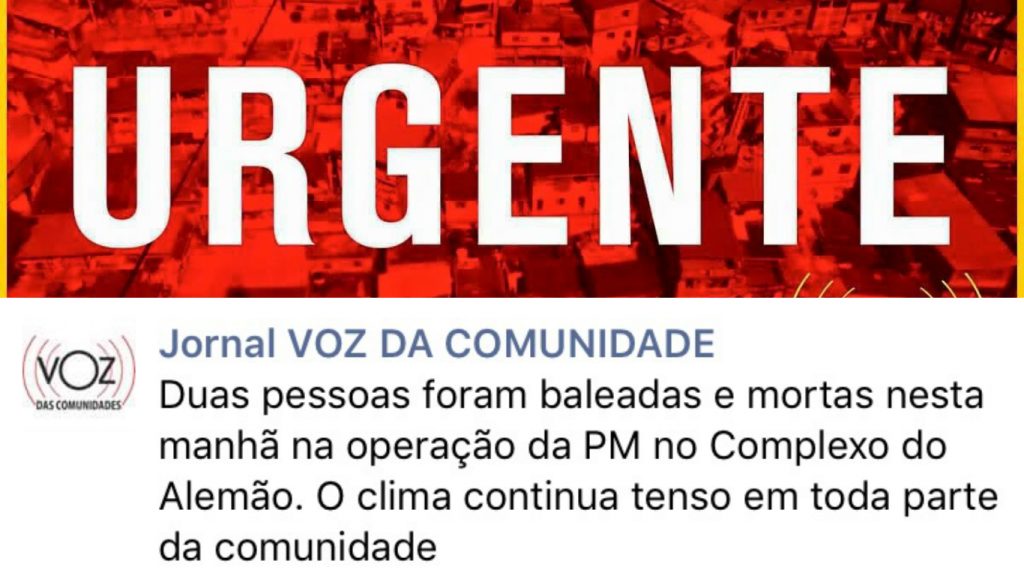

Yet, in the months leading up to the Olympics and continuing throughout the Games, many of Rio’s favelas experienced extended periods of intense violence. Frequent police operations and near-daily shootings in Alemão in recent weeks have led some residents to denounce the current situation as a “state of war.” A Facebook alert posted by Alemão community newspaper Voz das Comunidades just after 10am on #StopFavelaStigma day highlighted the impacts of misguided policies that are based on and justified by stigma: “Two people were shot and killed this morning in a Military Police operation in Complexo do Alemão. The tense climate continues in all parts of the community.”

Like Daiene in Alemão, community journalist Thaís Cavalcante of Complexo da Maré has actively worked to present an alternative narrative about her community in the face of mainstream media coverage that sensationalizes violence and depicts Maré as an inherently criminal space. Featured in an episode of WNYC’s On the Media, Thaís described: “Coverage that talks as if violence is the only thing that happens here… This kind of coverage is used to affirm certain policies of the state towards us.” Residents have taken action to combat oppressive actions taken by the State, mobilizing through initiatives like the “We are From Maré. We Have Rights!” campaign to inform citizens of their (often denied) rights in the context of police operations.

While tensions run high in Alemão and Maré with the onset of the Olympic Games, selective press coverage during the Olympic period has resulted in a media frenzy. Often, mainstream international outlets frame Rio’s violence only insofar as it affects tourists in the city’s South Zone, while ignoring how violence is a deeply-ingrained, systemic and structural phenomenon with repercussions for local residents extending far beyond the closing ceremony of the Games.

Catalytic Communities‘ Research Coordinator Cerianne Robertson tackled the misperceptions often reproduced by foreign journalists in her recent article “How Not to Write About Rio” published in POLITICO: “Yes, most favelas lack adequate sewage infrastructure, and some favelas are sites of drug trafficking and violence—symptoms of decades of government neglect alternating with government oppression. But contrary to what fans of ‘City of God’ or ‘Elite Squad’ or the Daily Mail might imagine, less than one percent of favela residents are involved in trafficking. Most favelas have no trafficking presence at all.”

Among popular misconceptions about Rio’s favelas is the idea that “favelas are slums,” as RioOnWatch contributor David Robertson highlights in his myth-busting Buzzfeed article. The #StopFavelaStigma campaign highlighted the complex question posed in 2015 by The New York Times Brazil bureau chief Simon Romero who tweeted: “Seeking better options than “slum” for translating favela. How to concisely explain such complex, vibrant places?”

While translating favela as “slum” is problematic because it suggests the condition of misery or depravity, other terms are similarly inaccurate: “shantytown” denotes a condition of precariousness in the form of “shanties” or shacks; “ghetto” alludes to residential segregation along racial or religious lines; and “squatter settlement” implies illegality. To accurately write about favelas, we should avoid these lazy, judgment-laden translations and just call them favelas.

Valuing qualities of favelas

While favelas are uniquely Brazilian, the stigmatization of low-income neighborhoods (in ways such as labeling them as slums) is a global phenomenon. From the South African Elimination and Prevention of Re-emergence of Slums Act to the “Cities without Slums” slogan accompanying Target 11 of UN Millennium Development Goal 7, it’s important to identify the negative views associated with the word “slum” and, moreover, to recognize that eradicating informality is not a viable nor socially desirable urban solution.

Accurately writing about favelas, however, involves more than just avoiding the tendency to blatantly fetishize violence—or on the other extreme, the tendency to romanticize poverty. Understanding Rio’s favelas must begin with an examination of the historical context in which favelas emerged and have developed over more than 100 years. The short film produced by Catalytic Communities called “What is a Favela?” traces the history of favelas in Rio, from describing the origin of the word “favela” to exploring the diversity of these urban neighborhoods in present day.

As architect Justin McGuirk poignantly inquires in his book Radical Cities: “When will we come to terms with the fact that the favelas are not a problem of urbanity, but the solution?” Favelas, and other informal settlements, must be understood not as temporary but rather as integral features of the urban landscape that have positive assets and require long-term public policy solutions.

Professor Justyna Karakiewicz of the Melbourne School of Engineering describes some of Rio’s favelas’ defining (and desirable) characteristics: they are “flexible and adaptable in their operation and use.” Similarly, Jorge Luiz Barbosa from Observatório de Favelas elaborates on positive favela qualities in an article for O Dia: “The favela is a territory of experimentation, simplicity, and challenges. Looking from afar, we don’t identify monumental cultural facilities… But when we get closer, the plurality of inventions and practices that give meaning to human existence are revealed.”

While Rio’s favelas are sometimes portrayed as sites of abject poverty, they represent working-class affordable housing options for about a quarter of the city’s population. In fact, a 2015 study by Data Popular showed that 65% of favela residents consider themselves middle class.

Yet, in a city where the cost of living has surged over the past five to ten years, intense real estate speculation has accelerated the process of gentrification—principally affecting South Zone favelas like Vidigal. Potential solutions to mitigate these processes include legal protections and collective land titling. In other cases, urban development in the city—catalyzed by real estate speculation and justified under the pretext of the Olympics—has resulted in traumatic forced evictions, most notoriously that of Vila Autódromo bordering the Olympic Park in Barra da Tijuca, West Zone.

Forced removals entail more than just physical damage as houses are destroyed. Former Vila Autódromo resident Jane Nascimento reflects that “Homes are not built with money, they are built with love.” Vila Autódromo, however, is not merely a “casualty” of the Olympic process—rather, it is a symbol of resistance showcasing the power of strategic community organizing.

Creative solutions

Resistance, activism, leadership and creativity are defining characteristics of favelas. Diana Anastácia of the cultural production collective Fortaleceu Produções in Jacarezinho, in the North Zone, contributed an article to RioOnWatch for #StopFavelaStigma day titled “Jacarezinho from a Resident’s View” about resistance cultivated in the favela: “Some examples of the cultural potential in the favelas are the residents of Jacarezinho who responded to the abandonment of the community by deciding to create something themselves.”

One manifestation of the do-it-yourself spirit that Diana describes is the concept of the mutirão, a collective action in which residents mobilize and join together to address community needs. For example, residents of Vila Kennedy in Rio’s West Zone partake in “a collective clean-up effort… every rainy day in summer and winter, as the rain causes earth and dirt to fill the water gully.”

In Complexo do Alemão, community-based organization Instituto Raízes em Movimento has led a series of collective action projects to repurpose abandoned public spaces left behind by the Growth Acceleration Program (PAC) constructions, and the program’s inability to meet community needs arguing what the community wanted was “not possible to do…here.” Coordinator Alan Brum describes the value of these community-constructed public works, produced by residents of Alemão with the support of university and NGO partners: “We want to prove that it is possible to achieve technical quality while at the same time taking into consideration what residents want for the space. The result is also a political weapon, to be able to say, ‘You told us that it’s not possible to take into account what residents want—and how they want things—and at the same time maintain technical quality. It is possible.’”

While some favelas do contend with poor physical and environmental conditions due to decades of government neglect, others are exemplary models of sustainable urban development. Launched at the Rio+20 United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development in 2012, Catalytic Communities’ short film “Favela as a Sustainable Model” showcases positive qualities of informal settlements, principally Rio’s favelas and how favelas can inspire more a more sustainable development paradigm in the city as a whole.

In Morro da Formiga, for example, a favela nestled between the Tijuca neighborhood and Tijuca Forest in the North Zone, environmental projects thrive, ranging from a community-managed water system servicing homes with natural spring water to an impressive gardening project. Another point of interest for sustainable favela-based initiatives is Vale Encantado, a small favela in the Tijuca Forest near Alto da Boa Vista, where the residents’ cooperative has spearheaded the construction of a sustainable sewage treatment bio-system.

This innovative solution to waste has garnered international attention, rendering Vale Encantado the principal case study for LEED-UP (LEED for Upgrading Informal Developments)—an informal offshoot of the Green Building Council’s LEED green development ranking system. Similarly, despite the claim to environmental and social sustainability made by the Olympic Athletes’ Village Ilha Pura, nearby favela Asa Branca ranks 28% higher when measured against the LEED Neighborhood Development (LEED-ND) criteria, beating the certified athletes’ village to earn “gold” in sustainability.

More informality and creativity, less criminalization

Just as stigma distracts from the potential for favelas to inspire sustainable development practices, stigma can inhibit recognition of favelas as hubs of creative production and cultural expression. In the words of Jocemir Moura dos Reis of Complexo do Chapadão, in the North Zone: “Our greatest challenge is the fact that people in general don’t see this as a cultural region and therefore don’t adopt this way of life. The impression is that music, arts, poetry, literature are not in the scope of our people, the local residents of our neighborhood.”

Debora Pio writes in an article for Viva Favela: “Maker culture (do-it-yourself) has always had a presence in the favelas, whether through a lack of resources which ends up enabling creativity, or through the great need of residents to reinvent their day-to-day life.… Why not value these skills?”

Musician Rodrigo Souza of Maré also attests to this cultural richness: “Here it’s not just guns, it’s not just drugs, it’s not just the police. There are also artists, there are also people who work, people who struggle daily, the truth is that they’re the majority of the people here… even with you living in a favela, you can still be an artist, you can still consume art. It’s not just the privilege of the middle class and the bourgeoisie, it’s the right of every citizen.”

From photography collective Imagens do Povo to the local projects featured in the film festival Reimagine Rio and to the YouTube video series Favelados Around the World, residents of favelas across the city work to defy stereotypes and deconstruct misperceptions about favelas and the diverse cultural productions that emerge from them.

At the same time that favelas are stigmatized, favela culture has been increasingly appropriated by mainstream society. Most recently, a favela landscape served as the aesthetic backdrop to Olympics opening ceremony, in which funk was prominently featured despite it being a criminalized cultural expression in favelas. Diana Anastácia of Fortaleceu Produções articulates: “We see the sharp dichotomy between the favela and the asphalt (formal city)… for the local, black resident, it is impossible to take part in funk, the principal cultural creation of the favelas, despite being born part of the funk movement. In contrast are the parties that take place elsewhere in the city… places of privilege and of the privileged, who enjoy the beat and essentialize and stereotype the hard and resistant reality of the favelas.”

The criminalization of culture born in favelas is one manifestation of the criminalization of poverty, a process by which individuals and groups face systemic prejudice and mistreatment based on their economic circumstances. For example, social scientist Priscila Loretti from UERJ describes the effects of regularizing electricity after the installation of the Pacifying Police Unit (UPP) in Santa Marta, in Rio’s South Zone: “Without public policies that are appropriate to people’s reality, they end up being pushed to the social margins, contributing once again to reinforce the stigma of the favela as a place of crime and informality.”

Catalytic Communities’ Executive Director Theresa Williamson elaborates on the social and economic repercussions of the criminalization of poverty in a recent interview with Guernica Magazine: “There is nothing inherent in [favelas] that produces criminality. The facts are that the state has neglected them, leaving them as easy targets for organized crime; that the citizens of favelas are criminalized so they lose their jobs and turn to organized crime; that we had a stagnant economy in Rio for much of the last forty years and now we’re back there again.”

Discriminatory practices—such as denying employment opportunities based solely upon one’s place of residence—are real social and economic consequences of favela stigma. RioOnWatch’s “Language of the Favela” series explores how language is another way that perceived social identity may be used as a pretext for discrimination: “Distinguishing between the ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ way to speak Portuguese can be a simple way of rationalizing discrimination and dehumanization.” These types of discrimination serve to create false associations between residence in favelas and negative personal characteristics (such as untrustworthiness or a lack of education), revealing deeply rooted class and race-based prejudices that continue to linger.

Diverse media challenging favela stigmas

Yet, time and time again, residents and community activists in favelas across the city refuse to let these discriminatory practices and stigmatizing narratives define them. As Adriana of Complexo da Mangueirinha in Greater Rio’s Baixada Fluminense describes, “We are already discriminated against for being poor, for being black. But if we allow that into our lives, we aren’t going to move forward.”

Community journalist Juliana Portella used #StopFavelaStigma to tag this poem, composed by Jessé Andarilho, known as #marginow: “I don’t want to die by gunshot / I refuse to, I withdraw / Police kill me and I become a criminal / Criminals kill me and I become a snitch /…/ My color makes me a suspect / My class condemns me / I just want more respect.”

Community media group Maré Vive shared a poem by rapper Cleiton Oliveira. The first stanza powerfully denounces the subtle and overt ways that racism has historically permeated Brazilian society: “Being black in Brazil is tough / That crooked look, the jokes are painful / I won’t pretend it doesn’t bother me, it does / For 500 years they’ve shut doors / The whippings continue, just that they’re silent.”

Beyond denouncing violence, favela residents play an essential role in stopping favela stigma by shedding light on positive attributes of their communities. Carla Siccos from community media group CDD Acontece in City of God, in the West Zone, elaborates: “The mainstream media only look to CDD Acontece when bad things happen here. We have many good things here. There are beautiful stories that people make happen. There are brilliant people here in the community who merit being featured. I don’t want only CDD Acontece to show these things, you know? I want others to see these people and know about their work.”

While many community-based media groups are rightfully critical of mass media, some mainstream international press outlets have been working to shift the lens through which Rio’s favelas are represented. The New York Times produced the recent video “Brazilian Badminton Sways to Samba” which highlights an initiative that embodies the creativity and innovation found in Rio’s favelas. Vox launched an excellent video exploring “Inside Rio’s favelas: the city’s impoverished, neglected neighborhoods.” Finally, The Guardian has taken historic steps to #StopFavelaStigma with its “View from the Favela” series, featuring contributions from young community journalists Michel Silva from Rocinha, Daiene Mendes from Alemão, and Thais Cavalcante from Maré.

What’s especially potent about these recent pieces of journalism—amid a sea of stigmatizing media narratives—is that they’ve offered an international platform for residents of favelas to speak for themselves.

Favela residents on social media

For the #StopFavelaStigma campaign residents of favelas were invited to reflect on their communities and respond to stigma by posting on Facebook and Twitter using the hashtags #MinhaFavelaÉ (#MyFavelaIs) and #MinhaFavelaNãoÉ (#MyFavelaIsNot), as well as #MinhaFavelaEra (#MyFavelaWas) in cases of evictions.

Using #MinhaFavelaÉ, Thainã de Medeiros of Coletivo Papo Reto in Alemão posted: “#MyFavelaIs potential! We are more than this Civil Police operation that took place today, which took the entire community of more than 200,000 people hostage in a war on drugs.” Linking to a video produced by young residents about what it means to be a “favela maker,” he continued: “My favela produces these people here who are creating, inventing and bringing solutions that will benefit everyone! There isn’t Rio culture without the favela! Try looking, you won’t find any expression of Rio that hasn’t passed by here! The State and corporations ignore us, silence us, but they know how to use our forms of expression. They know how to profit from this! But no, we aren’t foolish! We are makers of the favela!”

Gilmar Lopes, founder of the Sociocultural Eco-sport House in Morro dos Cabritos in the South Zone wrote: “My favela is a marvelous place surrounded by nature. It’s where I was born, where I grew up, and where my roots are!”

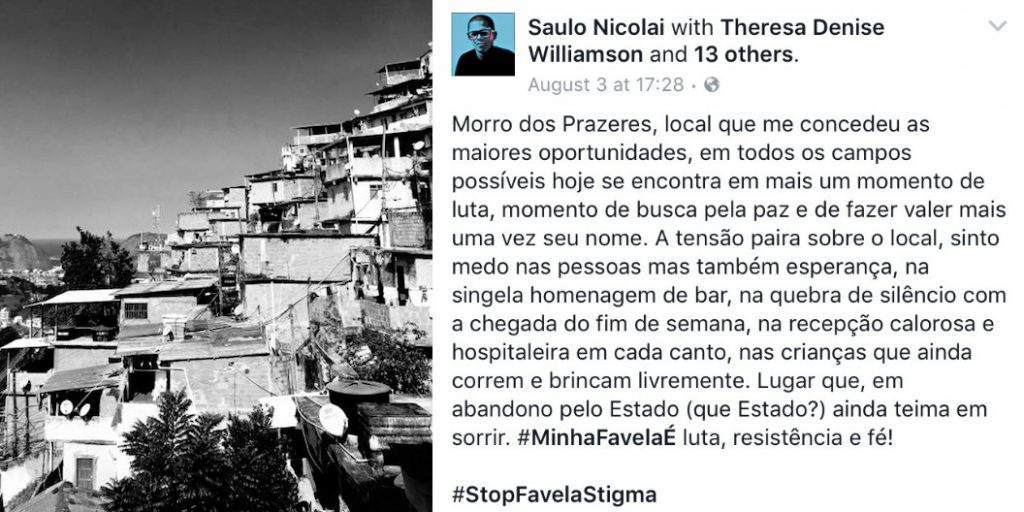

Photographer Saulo Nicolai posted a photo of his community with the caption: “Morro dos Prazeres, the place that gave me the greatest opportunities in all possible ways, finds itself today in a moment of struggle, a moment of seeking peace and to make its name worth something once again. Tension hovers over the place. I feel that people are afraid, but also hopeful, in the modest tribute at the bar, in breaking the silence when the weekend arrives, in the warm and hospitable reception at each corner, in the children who still run and play freely. A place that, abandoned by the State (what State?) still insists on smiling. #MyFavelaIs struggle, resistance, and faith!”

Thaís Cavalcante wrote “#MyFavelaIs free” and shared a photo of residents strolling along the notoriously busy Avenida Brasil highway taken on a night when it was shut down and empty for construction.

Community journalist Renan Schuindt from Costa Barros in the North Zone posted the first testimony with a #MyFavelaIsNot hashtag. He wrote: “I just took a walk here in Costa Barros and exactly at noon, the favela seems like a ghost town. Fear does this to people. It’s the worst when the fear that we feel is generated by the presence of those who should provide the opposite sensation. I only hope that this time we will not have to lose lives in order to give security to those who don’t know what in fact happens here!!!! #MyFavelaIsNot a minefield!!!”

Finally, utilizing the #MyFavelaWas hashtag, former resident of Vila Autódromo and Candomblé practitioner Heloisa Helena Costa Berto reflected upon her experience of being evicted from her home, which doubly served as a religious sanctuary, during the Olympic preparation process. Heloisa wrote: “#MyFavelaWas a sacred place of rest from the quotidian war / A scene of light play in the reflection of the Lagoon at nightfall / The peace that resuscitated my wounded heart. #MyFavelaWasLikeThis.”